石床屏風

- 中国

- 中国・北朝-隋時代

- 6世紀後半期-7世紀

- 白大理石

- H-62.3 D-6 W-53.4

この浮彫りの施された大理石の板は埋葬用の寝台の背面を飾ったもので、そこにはホラズムの女神、ゾロアスター教の葬送儀礼といった、中央アジアの風俗が描き出されている。それは大陸を往来し中国人と結婚し旅に没した墓主、おそらくソグド人と思われる人物の一生を活き活きと描き出したものであると想像され、古代ユーラシアの文化交流を考える上で大変重要な作品である。

Catalogue Entry

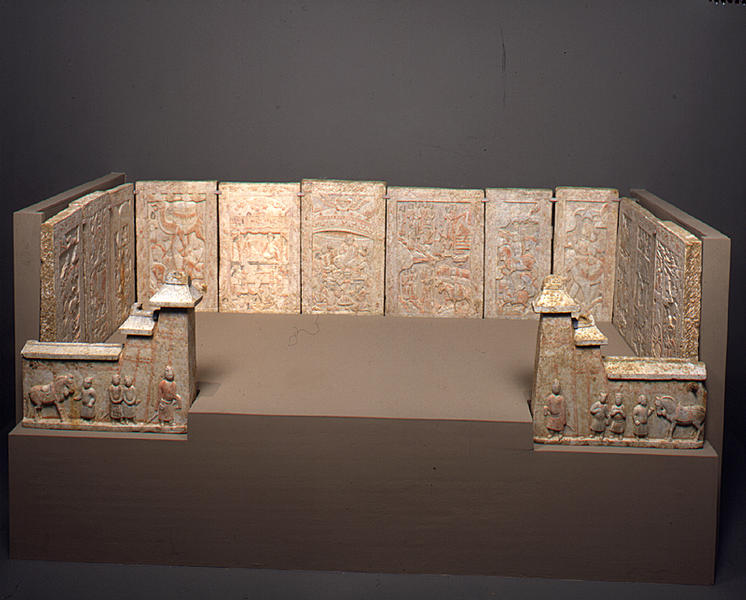

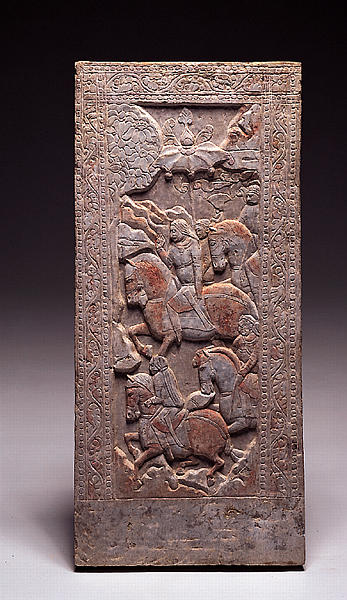

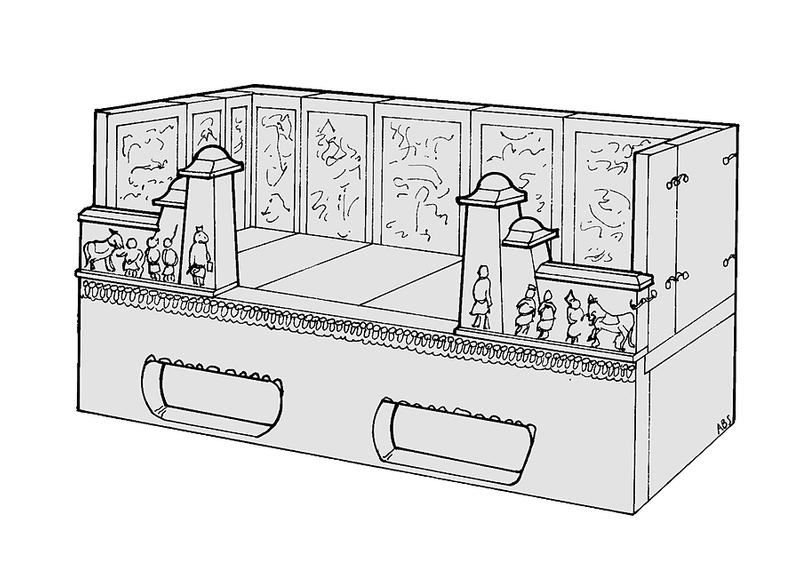

Said to have come from a tomb in northern China, these panels and gateposts originally stood on a rectangular coffin platform, now missing. The panels formed the two sides and back, and the towers at the front framed an entrance, as shown in figure 1.1 The reconstructed couch is similar to several funerary couches that have been excavated in northern China; the most recently excavated one was found in Tianshui in Gansu province, in northwest China.2 It does not have gateposts, but other known couches have them.3 These couches were created to support the remains of the deceased, and show a strong resemblance to Chinese domestic furniture, particularly to the formal sitting couch (chuang or kang) and the canopied bed (chazuchuang).4

During the fifth through seventh centuries burial practices in north and northwest China included the use of such couches as part of tomb furnishings. Tombs were often multichambered, recreating living quarters, and the funerary couch was placed in the back burial chamber, corresponding to the bedroom of the deceased. The two gateposts at the front of the couch refer to separate architectural forms, each with its own function. One is the chueh, a pair of high towers that mark the entrance to the burial site, the other, the towered entrance to a Chinese house.5 As the two gateposts are placed on the front edge of the couch they create a symbolic monumental entry into the space formed by the side and back panels, delineating the special status of the occupant in death as the formal sitting couch defined it in life.

Carved in relief on each of the eleven panels of the Shumei couch are lively events that do not draw upon typically Chinese subjects and symbols found on mortuary furnishings in the northern or southern regions at this time. These images are foreign and exotic, depicting almost exclusively non-Chinese ethnic groups engaged in a wide variety of activities.6 Through their precisely rendered physiognomies, hairstyles, details of dress, and objects such as musical instruments, we can distinguish specific ethnic or national identities. To date, there is only one other set of stone slabs from a funerary couch, reputedly found in Zhangdefu in northern Henan province, with imagery carved in low relief devoted to non-Chinese ethnic groups engaged in banquets and processions.7 Both sets of stones, the eleven white marble panels of the Shumei couch and those said to be from Zhangdefu, manifest the exotic environment so pervasive in the Northern Dynasties-region from the mid-fourth through the sixth centuries. Also linking these panels to those from Zhangdefu are the undulating foliate vines that frame each scene and the pictorial device of cropping figures and architecture so that many appear only partially within the frame.8

The sixth century in China is part of an historically and artistically complex period. Unstable and not well documented, it falls between China's two great dynasties, the earlier Han (208 B.C.-A.D. 220) and the later Tang (A.D. 618-906). During the fourth through sixth centuries, north China was completely overrun by seminomadic peoples whom the Chinese called "barbarians." Successive waves included Turk tribes, Tibetan groups, and the Xianbei, a proto-Mongolian people. By the late fifth century, a part of the Xianbei people, the Tuoba, provided more stability by controlling significant parts of northern China.9

In spite of political instability, foreign relations and trade were maintained, and envoys, merchants, and Buddhist monks arrived from Central Asia across the Silk Route. Of the merchants coming from Central Asia, the dominant group seems to have been Sogdians, an Iranian people who lived in the area corresponding today with the Central Asian republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. This area was known in ancient times as Sogdiana and contained a number of important cities, such as Panjikent and Afrasiab, or ancient Samarkand.

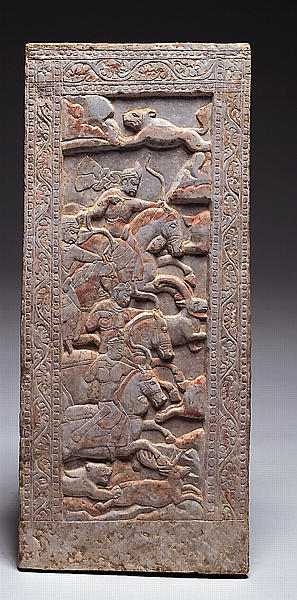

Reconstruction of the couch shows that three panels formed the left side (A-C), six panels composed the back (D-I), and two panels the right side (J-K). The panels were attached one to the other by a series of iron pins and loops set into the backs of the stones, which were hooked together.10 The first panel on the left side, A, the one closest to the left gatepost (1) is of a hunt in which four mounted archers shoot at fleeing game. These archers recall numerous images of royal mounted hunters depicted on silver plates from Sasanian Iran.11 Characteristic of these Sasanian royal images are long ribbons that flutter behind the king's crown. Although two of the hunters on the Shumei panel also wear long, fluttering ribbons, their dress and physiognomy distinguishes them from Iranians. In their facial features and flattened head they resemble Hephthalites, a Hunnish people who in the fifth century defeated Sasanian Iran and dominated Central Asia, including Sogdiana, for the next hundred years; figures with similarly shaped heads appear on Hephthalite metalwork.12

The hunt takes place in a rocky landscape, as does every scene in the remaining panels. This landscape often contains flowers and foliage, an occasional tree, and is often populated by a variety of animals. Some of the scenes on a given panel are unified compositions describing a single event, while others depict two distinct events, one above the other. In such cases, the landscape in the form of a rocky ledge serves to separate the events.13

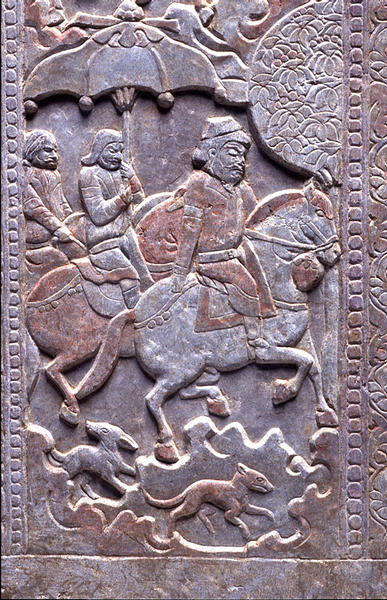

The center relief on the left side, B, shows two horsemen in the upper register. They wear tall, fez-like caps and the double-lapeled coats typically worn by Central Asian and Turk peoples. In the lower register, a riderless horse stands under a large parasol, with four figures behind it, and another figure, on the left, kneels before it and offers a cup up to it. The distinctness of these upper and lower scenes is established not only by a rocky landscape and the parasol, but by the orientations of the two groups: the twp horsemen above move to the right while the riderless horse faces to the left.

Riderless horses are found in Chinese mortuary art, particularly of the fifth and sixth centuries. They are represented by ceramic tombs figurines, in wall-tiles and wall-paintings, and even on stone panels from mortuary couches. In China, this image of the riderless horse is typically associated with the burial of high-ranking officials, usually from the military. An important example appears in a wall-painting from the tomb of the Xianbei general, Luo Rui. That and other horses from his tomb each have a tassel hanging from their necks, a feature shared by the riderless horse on the Shumei panel, as well as by horses in other panels. Such tassels seem to be either of Sogdian or of Turk origin, and are associated with the horses of important people; in addition to the Chinese examples, tassels are worn by horses of important people in the wall paintings at Sogdian Panjikent and Samarkand.

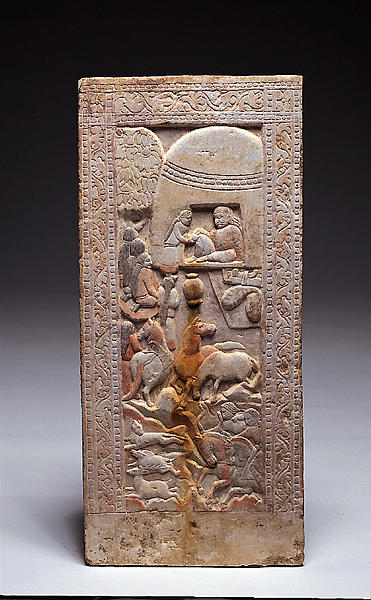

The third and last panel on the left side, C, is an encampment scene. A large figure sits in a domed tent and is served by attendants while a group of riders hunt below. This domed tent is a yurt, the collapsible felt home still used today by Turkic peoples. Not only does the yurt identify them as Turks, their long hair, divided into long strands or braids and bound at the neck, also marks them as these nomadic people. Among the wall-paintings at Samarkand that show foreign delegations appear similar long-haired figures that are identified by inscriptions written directly on the paintings as Turks.

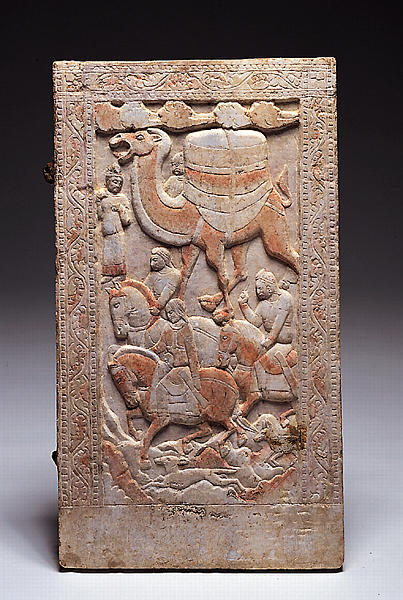

Moving to the six panels that form the back of the couch, the first on the left, D, shows a camel laden with goods, accompanied by long-haired Turks on horseback. Camels were the main means of transport for goods moving back and forth across the Silk Road between Central Asia and China. Their importance is reflected in Chinese mortuary art of this period: numerous mingqi, clay sculptures made specifically to accompany the deceased, are heavily laden camels. Above the camel, clouds move to the left, recalling the widespread appearance of cloud wisps that below across the sky in Chinese pictorial imagery of the sixth century.

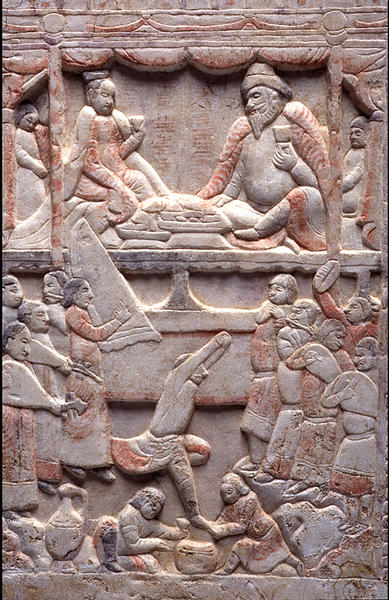

The next panel, E, is a marriage feast for a portly, bearded Central Asian gentleman and a non-Central Asian lady, most likely Chinese. They are seated on a Chinese couch or kang toasting each other. As part of the celebration, a troupe of musicians and a dancer perform in front of the couple. This part of this panel is especially important for Central Asian connections. The orchestra and vigorously moving dancer is a recurring image on ceramic pilgrim flasks produced during the sixth through ninth centuries in China during the Northern Qi and Tang dynasties. On the flasks and the relief the dancer seems to perform what the Chinese called huxuan or “Sogdian whirl.” Central Asian music and dance were extremely popular in China from the sixth century through Tang times, and male and female dancers were imported from Samarkand and Tashkent in Sogdiana. They were so popular that a famous general in the Tang emperor’s court was renowned for his ability to dance the Sogdian whirl despite weighing 400 pounds. Another Sogdian connection is the ewer of characteristically Sogdian form that appears in the lower left near the two kneeling servants.

The third panel of the back, F, has two levels: in the center of the upper one a figure stands before a fire altar wearing the padam, the white veil that Zoroastrian priests wear so as not to defile the sacred flame. To his side is a dog, which plays a central role in the Zoroastrian funerary rite called the sagdid. In this rite, the dog is made to look at the body of the deceased, since its gaze is believed to drive away the spirit of defilement. Directly behind the priest is a group of men, four of whom kneel and hold knives to their faces or foreheads. None of these male figures is Chinese, and, indeed, their appearance and the act of stabbing themselves recall a famous scene of mourning from Sogdian Panjikent.

The fourth panel, G, is a second banquet, this one most likely representing the deceased himself. The large figure of a Central Asian sits cross-legged beneath a magnificent floating canopy, which indicated his high status. This canopy with its jeweled and beribboned lotus finial is reminiscent of the elaborate canopies that define the central images in Chinese Buddhist paradise scenes. The man holds a cup and is flanked by servant figures. In front of him, other servants prepare food for the banquet. In contrast to the Central Asian man in the marriage feast, this banqueter is clean-shaven, has curled hair, and wears a different type of hat. Of interest is the variety of ethnic types represented by his servants, distinguished by their clothing, hairstyles, and facial features.

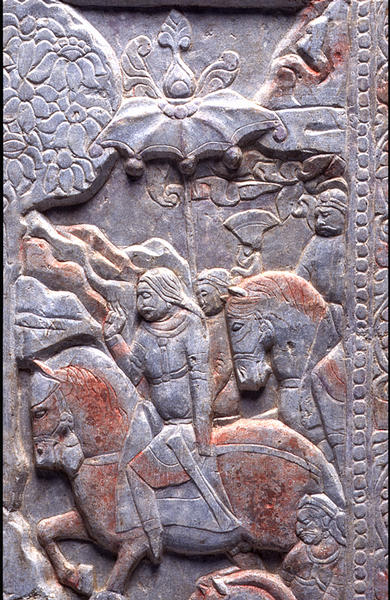

The two reliefs to the right of the banquet scene ? the last two of the back of the couch ? both show processions advancing through the same rocky landscape. One, H, shows a procession of Turks and Central Asians on horseback, while the other, to its right, I, depicts Hephthalites mounted on an elephant. The importance of the central figure in each panel ? a long-haired Turk, and an elaborately crowned and beribboned Hephthalite ? is signified by his placement and a parasol held directly above his head. Each personage has his right hand raised in a fist with index finger extended, a well-known gesture of respect in the Iranian / Central Asian world.

The first panel on the right side of the couch, J ? the one at a right angle to the elephant-rider ? is a double panel with two separate scenes side by side. On the left, two groups on horseback move in opposite directions. At the top, a non-Central Asian lady, wearing an unusual tall headdress, rides toward the left, accompanied by two attendants. Below, riding to the right, is a Central Asian man, also accompanied by two attendants as well as two dogs. One of his attendants holds a parasol over his head, indicating the man’s high status. Another such sign is the tassel that hangs from his horse’s neck; a similar tassel also hangs from the neck of the lady’s horse, showing her importance. A procession similar to that of the male rides appears on several stone panels from the funerary couch from the mid-sixth century that is said to come from Zhangdefu, near what was the capital of the Northern Qi dynasty. The panels from Zhangdefu also depict non-Chinese peoples; but unlike the Shumei panels, the number of ethnic types is limited. However, the main figures in both a Zhangdefu panel and this Shumei panel have much in common: the way they sit on their mounts, their clothing, hairstyle, and even the parasol that is held above them.

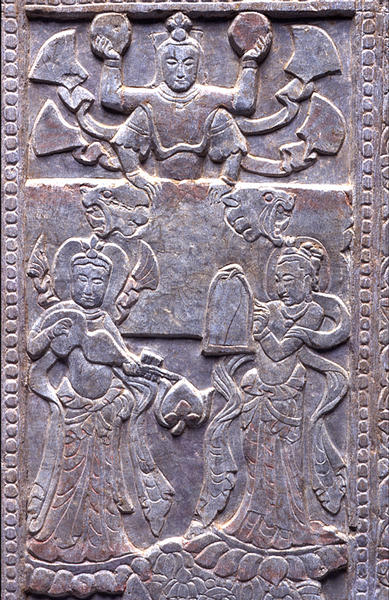

The relief carved on the right side of panel J seems to have some eschatological significance as it appears to show two distinct realms: the heavenly and the earthly. In the upper, heavenly realm appears a four-armed goddess, two arms raised to hold the sun and moon, and two arms resting on a parapet decorated with two lions’ heads. She looks down on two acolytes, probably Buddhist bodhisattvas, each of whom plays a musical instrument and stands on a lotus flower. In the lower, earthly realm, musicians accompany a female dancer.

The goddess is to be identified as Nana, whose images are widespread in Sogdiana and in Khwarezmia, to the north, in painting, stucco, woodcarving and metalwork, and where she is specifically associated with the funerary cult. In all her representations she sits on a lion throne or directly on a lion, with symbols of the sun and the moon held in two of her four arms. This image of Nana traveled eastward as well, in the Buddhist art of Chinese Turkestan. In the Shumei relief, the lions’ heads are an abbreviation of Nana’s animal attribute, while one of the deity’s discs retains its red paint to represent the sun; the other probably contained a red crescent moon, which is no longer visible.

Moving down to the earthly realm, the image of a Central Asian orchestra seated on mats and flanking a female dancer probably doing a Chinese “sleeve dance” finds a remarkable parallel in a scene carved on the base of a Buddhist stele from Xi’an in Shenxi province in central China. The Xi’an piece shows the same scene with two different orchestras and two different dancers: on the right, Chinese musicians sit on mats while a female figure performs the sleeve dance, and, on the left, a Central Asian orchestra accompanies a Central Asian male dancer performing the Sogdian whirl. This scene on the Xi’an base, like the panels of the Shumei couch, manifests the exotic elements so pervasive in the Northern Dynasties of China.

The last panel on the right, K, the one closest to the front of the couch and abutting the right gatepost, is the most “Chinese” of all the scenes. Of its subject matter, the two-wheeled cart drawn by oxen is a standard feature in Buddhist cave-paintings and Chinese tombs from the fourth century on. Of particular importance is a painting from the tomb of the high-ranking Xianbei general Luo Rui, which depicts a similar high-canopied cart with attendants and banners. Especially noteworthy is the placement of the cart near the entrance of Luo Rui’s main tomb chamber, paralleling panel K’s placement on the couch right next to a gatepost, at the “entrance” to the couch. Also of note are the similarities of the shapes and decoration of the banners as well as the non-Chinese appearance of the attendants in the Lou Rui painting and this panel.

Panels A and K each about a gatepost, 1 and 2, respectively, and were attached to a hook that protruded from the front of each gatepost. The gateposts display features that are typical of Chinese architecture: double towers with hipped roofs, each topped by a characteristic double hook. Like the gateposts from the Zhangdefu couch, as well as other known examples, the towers are stepped, the taller one flanking the “entryway” and abutted by the shorter one which, in turn, is connected to a shorter section of wall. Architectural details of the tower walls are indicated by red paint. Carved in relief on each gatepost, across the lower portion of the towers and the wall, is a procession of four Central Asian and Xianbei men, one of whom leads a riderless horse. The men wear long belted tunics and boots; all but the groom who leads the horse have their hands covered by their long sleeves. The lead figure on each gatepost is distinguished by his height, placement, and dress. He is taller, stands apart, is framed by the mass of the larger tower, and wears a long sword. This type of procession of men with a riderless horse, as well as the architectural details, are paralleled on the Zhangdefu gateposts.

Who was buried in the tomb that housed this extraordinary funerary couch? The relief with the Zoroastrian funerary rite, the sagdid ceremony, provides an important clue. Sogdians, who were Zoroastrians, were among the major merchants who moved goods back and forth across Central Asia and China. They also established permanent communities in China and intermarried with the local populace which, at that time, consisted of mainly Xianbei and Chinese. Is it possible that this funerary couch was the repository of the bones of some Central Asian, most likely Sogdian, who died in China? When viewed in this light, the arrangement of the stones and the overall program that underlies it present a coherent and poignant story. The sagdid ceremony on panel F and the flanking the banquet scenes on E and G, form the visual focus of the entire couch: not only are they in the physical center of the back, they are framed by the two gateposts, which, when the couch is approached from the front, obscure the other back panels.

As the story unfolds, the marriage scene may refer to the marriage of the tomb owner’s father or grandfather with a local woman, the sagdid ceremony to the rites performed at the tomb owner’s death, and the banquet scene representing the tomb owner as a symbolic participant in the banquet that was held at the time of the funeral.

The two central panels in each of the sides of the couch, B and J (right), also refer to funerary rituals. That on the left, B, with the riderless horse occurs, as already noted, in both Sogdian and Chinese funerary contexts; that on the right, J, showing Nana, has connections with Sogdian and Khwarezmian funerary monuments, while the bodhisattvas and musicians are known from Chinese Buddhist paradise scenes. The other scenes involving hunts and processions of various Central Asian peoples no doubt reflect the peoples with whom the deceased had dealings and may even have attended his funerary rites. These scenes also find their counterpart in the processions of foreign peoples in the paintings at Sogdian Samarkand, which also have funerary connotations.

Before the Shumei funerary couch came to light, little pictorial evidence existed that directly reflected the rich ethnic tapestry that existed in sixth-century China: Buddhist monks traveling from Central Asia and India, nomadic invaders from the north, brisk movements of envoys and merchants from Sogdiana and farther west, and settlements of foreigners in Chinese cities. The Shumei couch has brought these people into sharper focus and has provided a rare glimpse of a Central Asian’s life in sixth-century China.

加彩大理石レリーフパネル