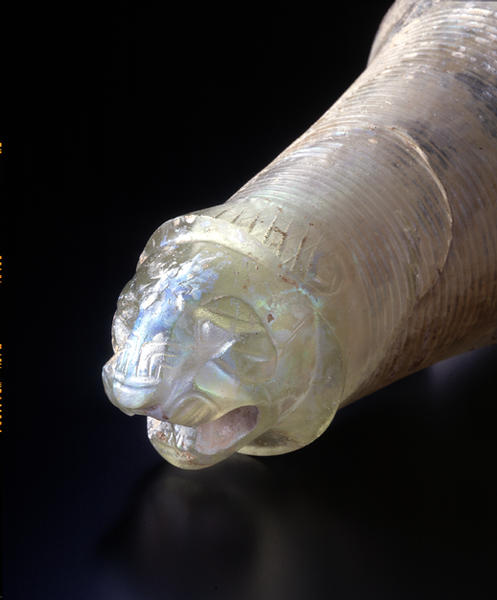

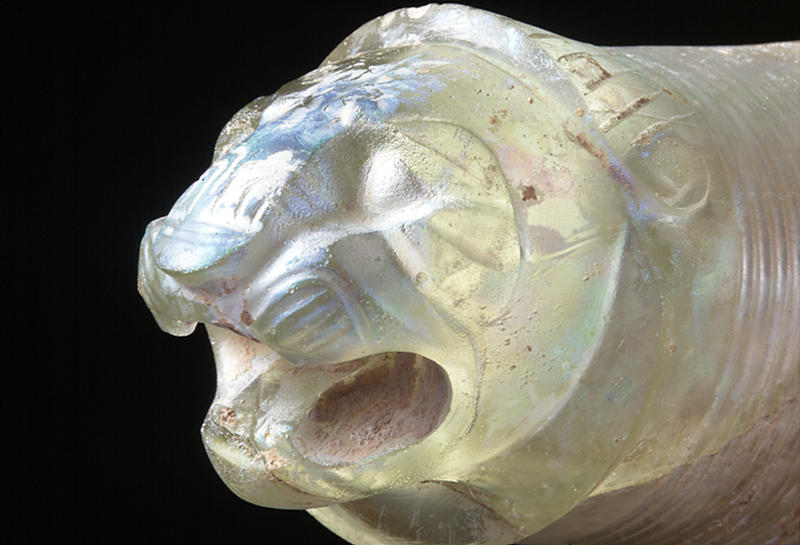

獅子頭形杯

- アケメネス朝ペルシア

- 紀元前5-紀元前4世紀

- ガラス

- H-17.1 D-11

伝イラン。前5世紀~前4世紀前半。

淡緑色透明ガラス。3部分からなる複合鋳型による鋳造法、あるいはロスト・ワックス法。冷却後、カットし、彫刻を施す。少なくとも2つに割れ、最近になって修復されている。割れ目を泥で塗って、隠す。ライオン頭部から畝状装飾がある胴部まで圧力が原因のひびが伸びる。右上の歯の先端が欠損(古代のものか)。わずかな銀化と不透明で黄褐色をした皮膜を有する。

比較的大型の容器で、装飾のない口縁に向かいトランペット状に広がっている。杯胴部には、平行線状の溝(畝)を36本丁寧に刻む。下部は口を開いたライオンの頭形に鋳造。目、鼻、鼻の穴、歯などの各部位は、旋盤を利用して彫刻された。

この珍しい杯(把手なしのシトゥラ)は、アケメネス朝の豪華ガラス製品が最も優れていた時代を象徴する逸品である。これに匹敵するガラス容器は、ペルセポリスで発見された作品1)1点のみである(後出)。ペルセポリスのガラス容器は、無装飾(?)の中間部分が失われた胴部と牡牛に襲いかかるライオンの前半身をもった湾曲したリュトンである。カットの質は極めて良く、この角杯の製作者の芸術的レベルと技術的レベルの高さを示している。残念ながら、この作品が製造された時期は特定されていない。しかし、ペルセポリスは前5世紀に絶頂期を迎え、さらに宮殿の建築は前518年頃ダリウス1世によって始まり、クセルクセス1世(前485―前465)とアルタクセルクセス1世(前465―前424)の下で拡張されたことを考えれば、ペルセポリス、スーサ、エクバタナなどの王家に付属する工房は、前5世紀に絶頂期にあったと判断するのが妥当であろう。以下に、イランで見つかったこの時期の豪華ガラス製品は、メソポタミアから輸入されたものではなく、西

( 多分アッシリアなど)から来た外国の職人、もしくは現地の腕の良い熟練工の作であることを示す。

アケメネス朝のガラス器

透明で豪華なガラス器の歴史は、前8世紀のアッシリアから始まる。この時期以前の容器と象嵌は、ファイヤンスや石など他の素材を模倣して、不透明または透明ではあっても色の濃いガラスで作られていた。アララク(シリア北部)、アッシュールおよびウルから発見された前15世紀から前14世紀に作られたコアガラスの香水入れ2)、エジプト第18王朝時代のコアガラスの香水入れ3)、さらに、エジプトやドゥル・クリガルズ(アガル・クフ:バグダッドの近く)などで発見された大量の象嵌は、古代に多彩なガラス製品が好まれたことの証拠である。このように、エジプトやメソポタミアでは、同時期に多彩なモザイクガラスが作られた4)。

珍しい水晶を模して透明のガラスやほぼ透明のガラスを作る試みが始まるまでには、以降少なくとも7世紀を経過しなければならなかった。ガラスから色を抜く薬品を探す必要があり、技術的にこの新しい素材を製造するのは容易なことではなかった。この技術が最初に確立されたのはニムルドで、前8世紀から前7世紀の変わり目頃だったと見られている。大英博物館に保管されている特に厚みをもったアラバストロンには、「サルゴン王宮」や「アッシリアの王」と読み取れる楔形文字が書かれている。このことは、このアラバストロンがサルゴン2世王(前722―前705)の王室のものであったことを示している5)。壺は、小振りながらも、緑色をおび、透き通っている。厚みは0.7~1.7センチである。また、ニムルドでは、鉢1点と半球形の器数点の他、約100~140点の碗の破片が発見されている。その中には、薄く、ほとんど透明のガラスで作られた製品もかなり多く含まれている。19世紀の50年代および60年代に発掘されたものの中には、非常に細かい彫刻を施し、カットされた透明なガラスの破片も数点含まれているが、このことは、前8世紀から前7世紀のアッシリアの奢侈品が非常に質の高いものであったことを物語っている。この作業場または同様の設備をもった作業場で作られた製品の1つに、トルコのゴルディオンにある少女の墳墓から発見されたほとんど透明なオンファロス・ボウルがある。この碗は、前8世紀の最後の25年間に製造されたと見られている。

ニムルドとゴルディオンで見つかったようなガラス器6)は、他の地域でも発見されている。ボローニャ、プライネステ、クノッソスのフォルテッツアで発見された半球形の碗、バビロンの浅い碗、スペインのアリセダ宝物の水差、そして、ボローニャのジアルディーノ・マルゲリータのアンフォラは、すべて、前7世紀のもので、アッシリアで作られたと考えられる。が、中には、例えばアリセダの水差のように、フェニキアで作られたとされるものもある。前6世紀から前5世紀に作られ、厚みがある、ほのかな緑色や灰色をおびた一連の細長いアラバストロンは、初期の「新しい様式」 のガラス器に分類されるべきである。

イランで発見された、または発見されたと言われている、事実上まったく色のない素材で作られたガラス器は、この初期の製品に続くものである。同様に、これらの製品は逆に、エーゲ海沿岸地域に透明ガラスまたはほとんど透明なガラスの製法を伝授し、多様な形をしたヘレニズム時代のガラス器製法に強い影響を与えた。

アケメネス朝のガラス器で最も重要な発掘物は、シカゴ大学のオリエント研究所が1931年と1934年に調査を行ったペルセポリスで発見された器である。エフェソス、アスライア(キュレナイカ)、イーリンゲン(ドイツ南西部)、ニップール、クルドシップスキー・クルガン、トリアレティ(ロシア南部)など、他の多くの地域でも別のガラス器が見つかっている。さらに、骨董市場から、いくつかの重要な品々が提供されている。鉢の形( さまざまな変形種がある)は、アケメネス朝のガラス器で最も一般的な形である。専門家による監修の下で発掘された品または個人のコレクションあるいは博物館が購入した品で、同質のものに分類されるものの中でも、図版59の獅子頭形杯は最も質が高い作品の1つに数えられる。

ペルセポリス宝物には、ほぼ全面的に「水のように透明な」ガラスで作られた最高質のガラスの破片が大量に含まれている7)。これらのガラス製品は、溶かして鋳型に入れて作った。そうして作られた品は、装飾品はもちろんのこと、鉢も、飾りや象嵌として使われたのであろう。発掘物には、およそ20個の鉢が含まれている。特に注目すべきものは、深い孤を描くようなアーモンド形をした膨らみをもつ器1点と、縦に畝状装飾が入った杯数点、そして獅子頭形杯の文様とまったく同じ文様をもつ装飾品1点である。他の破片には、水差や壺の把手、見事な彫刻を施した厚いガラス容器が含まれる。小さな装飾品の中には、美しい彫刻を施したものがあるが、これは、王家のアトリエで働く職人の技術の高さを証明するものである。

1959年、シラーズ大学のアリ・サミが、ペルセポリス・ラーマト山の麓で、牡牛を襲うライオンの前半身が付き、ほぼ透明のガラスで作られた素晴らしくかつユニークな角杯を発見した。この角杯は、地下約5メートルの、年代を特定できない地層から見つかっているが、ペルセポリス宝物を成す一連のガラス製品の1つであることは間違いない。角杯と獅子頭形杯、さらに他の鉢も貴金属または石でできた原型を元に作られている。例えば、獅子頭形杯は、イラン(ウルミア湖の南)で初期 ― すなわち前7世紀に作られた同じような形をしたマンナイの銀製の角杯8)と比べることができる。さらに、ロシア南部にある七兄弟(the Seven Brothers)のクルガンで発見された角杯や、かつてはシンメル・コレクションの一部を成し、現在はメトロポリタン美術館に所蔵されている前5世紀前半に作られた角杯をはじめとする貴金属製の角杯は、水平の畝状装飾を施した胴部、外に向かって広がる口縁、雄羊の前半身形を特徴としている9)。

表面に溝や畝の装飾を施した鉢の形をした装飾品は、角杯や獅子頭形杯だけではない。テサロニキ(サロニカ)の北部デルヴェニのB墓からは、ロータス文の高浮彫の下に水平に並んだ溝を施した透明なガラスの杯の破片が見つかっている。製造年代は「紀元前323/315年以降」とされているが、ペルセポリスで発見された畝状装飾を施した杯(前出)と密接に関係していることから、後期アケメネス朝の作品の貴重な1点とも考えられている。ベルリンやオックスフォードの例が証明するように、この種の器は、アケメネス朝の銀杯の忠実なコピーである10)。上に向かって広がる太い首をもったコーニング・ガラス博物館のガラスの壺(またはリュトン)の胴部は卵形になっているが、この胴部には、縦の畝状装飾が施されている11)。この製品は、前5世紀のものと推定され、イラクで発見されたアイベックスの形をした把手が付いたアンフォラなど、金属製の容器の形に似せて作っている。このアンフォラも前5世紀の製品である12)。

前述したように、アケメネス朝の器の形状は、金属製およびガラス製のものとしては最も一般的ある。製造時期がはっきりしたガラス器が複数あれば、獅子頭形杯の製造年代を歴史的にしかるべき時期に特定することが可能であろう。このような器の多くには、畝状装飾または中心の小円から放射状に広がる葉飾りが施してある。これらの器は、その形状により、数種類に分類できる。胴部は、浅いか比較的深いかのいずれかであるが、これらの器は、常に貴金属製の製品を模して作られた13)。我々は、このような品だけが、科学的監修の下に発掘された品と認定されるべきであると考える。事実上、これらの製品のすべてが透明なガラスで作られている。淡青色の素材を使ったものもあるが、これらは数も少なく、例外的である14)。

私が知っている最も古い時代のものと認められる品の中に、ベンガジの北東、キュレナイカのアスライアにある石造りの墓から発掘された畝状装飾を施した胴部と外にそり返る口縁を有する深鉢がある15)。この鉢と一緒に発見されたギリシア陶器から、墓は前5世紀後半のものと推定された。また、中心から放射状に広がる葉飾りを施したほぼ同じ形の器の破片が、グルジア西部のクヴィリラ川(古代ファシス)沿いのサイルケにある石造りの墓から発見されている。同じ墓で見つかった他の品々から、この墓は前5世紀中期のものに間違いないと認定された16)。マケドニアのアイネイアやヴェロイア17)、さらにロードス島18)からも同じような器が発見されている。これらの器は、前4世紀の最後の25年間に造られた墓から見つかっており、ギリシア製であると考えられるが、アケメネス朝に作られた古代製品の文字通りのコピーである。

書物でも有名なものに、エフェソスにあるアルテミスの神殿跡の盛り土の中からD. G. ホガースが発見した器がある。アルテミスの神殿は、前356年に焼失したと言われている。外にめくれ返る口縁を有した花弁状のこの器は、前5世紀に作られた器と似ていることから、前5世紀後半または前4世紀前半のものと認められる19)。しかしながら、まったくかけ離れた場所からも同じ種類に属する器が1点発見されている。ドイツ南西部のイーリンゲンの墓から見つかったガラス器である。透明なガラスで作られた、浅く、飾りのないこの器は、前5世紀中期のものに間違いないと考えられている20)。

ロシア南部、グルジア、ニップールからも、アケメネス朝のガラス工業の「発祥地」の製品とよく似たものが見つかっている。エフェソスの器と似た形状を有する2点の器が、クルドシップスキーの墳丘(マイコプの南)から、また、トビリシ―ティフリスの南西部を流れるアルゲティ川沿いのトリアレティ近くにある墓から、発見されている。クルドシップスキーのものは前4世紀、トリアレティ近くのものは、前6世紀後半または前5世紀に作られたとされている21)。また、1889年、折り重なる葉の文様がある深鉢の断片がニップールで発見されたが、残念なことに、無成層の地層から出土したために、年代は特定されていない22)。

前述のアケメネス朝のガラス容器に匹敵する製品はかなり多く存在していると言われている。長い間博物館に所蔵されていたものもあれば、骨董市場を介して、公共または個人のコレクションに入ったものもある。これらの品は、ケルン、コーニング、デュッセルドルフ、ジュネーブ、ハンブルク、イスタンブール、エルサレム、ロンドン、ミュンヘン、ナポリ、ニューヨーク、レーゲンスブルク、サンクトペテルブルク、トレドなどで保管されている。以前、サンジョルジ・コレクション(ローマ)にも1点存在した。さらに、別の数点が骨董市場にあった。現在もあるかもしれない23)。

鋳型を使って作られ、同じような装飾が施された無色の(ごく稀に淡青色をおびている)ガラス製品は、分かっている限りでは、アケメネス朝のイラン王家の住居近くに設けられた作業場で製造された。ニップールからドイツまでと、かけ離れた土地から多くの製品が発見されているが、大多数はイランで発掘されている。より正確に言えば、最も精巧な品々が見つかったペルセポリスから発掘されているのである。さらに、イランの職人によって作られたと言われている貴金属製の鉢は、事実上すべてのケースにおいて、ガラス鉢の直接的なモデルになった24)。その証拠は、ペルセポリスのアパダナのレリーフにたくさん見られる25)。

イランのガラス器に似た作品の記述を、前425年にアテネで初上演されたアリストファネスの「アカルナイ人」(37,5)に見ることができる。ここには、エクバタナにあるペルシアの宮殿でアテネの大使たちが「金とガラスの杯から甘い葡萄酒を飲んだ」26)と書かれている。この記述から、ギリシアでほぼ無色のガラスの製造が始まったのは、アケメネス朝の技術によるところが多いと推測される。かくて、無色のガラスは鋳型で形作られ、金と象牙で作られた巨大なゼウス像の象嵌に使われたのである。これらの象嵌は、オリンピアにあるフィディアスの作業場から発見されており、前435年から前425年に作られたものとされている27)。

イランの贅沢ガラス製品(製造施設はまだ発見されていない)の影響は、ヘレニズム時代のガラス製品に色濃く残っている。この種の優れた鉢は、マケドニア、ロードス島、デロス島などのエーゲ海沿岸地域では、前4世紀最後の25年間に初めて登場する。ガラス鉢はこれらの土地で作られていたようである。しかしながら、後期アケメネス朝の製品と前期ヘレニズム期の製品を分けるのは、必ずしも可能ではない。アレキサンドリアで作ったと思われるやや後期のヘレニズム期の豪華なガラス製品は、南イタリアにある素晴らしい設えを施した墓の副葬品の中から発見された。カノッサとタラントの宝物は、ヘレニズム時代のガラスの最も有名な発掘物の一部を成している。

ヘレニズム時代のものに分類されるすべての鉢は、形、技術、そして装飾のモティーフの一部において、イランガラスの原型なしでは存在し得なかった。アッシリアで前8世紀後半から前7世紀にかけて見られた技術進歩の恩恵も受けている。ペルセポリスや他の場所のガラス、さらにこの種類に密接に関係している多くの鉢、例えば獅子頭形杯は、最高級のイラン贅沢品の一部を成している。古代ガラス全史において、美学的センスと優れた職人技の面で獅子頭形杯に匹敵する水準に達した時代は多くない。

註:

01. 高15cm. テヘランのイラン・バスタン博物館 Av.Saldern, Glasrhyta, Festschrift f殲 Waldemar Haberey, Mainz 1976, 121-3, pl.32:1; S. Fukai, Persian Glass, New -York-Tokyo-Kyoto 1977, fig.8.

02. D.Barag, in: A.L. Oppenheim et al., Glass and Glassmaking in Ancient Mesopotamia, Corning 1970, 129-99.

03. B. Nolte, Die Glasgefaesse im alten Aegypten, Berlin 1968.

04. A.von Saldern, Mosaic Glass from Hasanlu, Marlik, and Tell al-Rimah, Journal of Glass Studies (=JGS) 8, 1966, 9-25; idem, Other Mesopotamian Glass Vessels (1500-600 B.C.), op.cit. Oppenheim et al. 1970, 203-28; Nolte, op.cit. 1968.

05. D. Barag, Western Asiatic Glass in the British Museum, London 1985, no.26.

06. A.von Saldern, Glass Finds at Gordion, JGS 1, 1959, 22-7, figs.1-2.

07. E.F. Schmidt, Persepolis (OIP 68), Chicago 1953, pl.41; idem (OIP 69), Chicago 1957, 91-3, 127-32, pl.66-7.

08. C.K. Wilkinson, Two Ancient Silver Vessels, Bull. Metrop. Mus. Of Art 15, Summer 1956, 9-15; The Pomerance Collection of Ancient Art, The Brooklyn Museum 1966, no.54.

09. H. Hoffmann, The Persian Origin of the Attic Rhyta, Antike Welt 4, 1961, 21-9, pl.11 (七兄弟クルガン出土のリュトン); Ancient Art. The Norbert Schimmel Collection (ed. By O. White Muscarella), Mainz 1974, no. 155. 更に獣の前半身をつ け畝文様を器体に施したアケメネス朝、主に5世紀の金銀器をも参照すべきである: 7000 ans d'art en Iran, exhib. Paris 1962, nos.638ff.,pls.53ff.; Traci. Arte e cultura nelle terre di Bulgaria…, exhib. Venice 1989, nos. 138 ff.

10. G. Hafner, Kretisch-Mykenisches in der spateren griechischen Kunst, Festschrift des R嗄isch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 3, 1953, pl.6:6; A. Oliver, Jr., Persian Export Glass, JGS 12, 1970, fig.10.

11. S. Goldstein, Pre-Roman and Early Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning 1979, no.250.

12. Pomerance Collection op.cit. 1966, no.59.

13. Oliver op.cit. 1970; D.F. Grose, Early Ancient Glass, The Toledo Museum of art, New York 1989, 80-1, fig.48.

14. ペルセポリス由来の器の把手: Schmidt, op.cit. 1957, pl.67:1; bowl with leaf petals in Corning, Goldstein, op.cit. 1979, no.251.

15. M. Vickers, An Achaemenid Glass Bowl in a Dated Context, JGS 14, 1972, 15-6.

16. George Makharadze, Mariam Saginashvili, An Achaemenian Glass Bowl from Sairkhe, Georgia, JGS 41, 1999, 11-7.

17. I. Vokotopoulou, Oi taphikoi toumboi tes Aineias, Athens 1990, 61, no.15 (tumulusⅢ, grave A); G. Touratsoglou, To xeiphos tes Veroia: symbole ste Makedonike oplopoia ton isteron klassikon xronon, Archaia Makedonia 4, 1986, 641-3, fig.5.

18. P. Triantafyllidis, New Evidence of the Glass Manufacture in Classical and Hellenistic Rhodes, Annales du 14e Congre`s de 1'Association Internationale du Verre 1998 (2000), 30-1 fig.5-7.

19. Barag, op.cit. 1985, no.46.

20. R. Dehn, Ein sp閣hallstattzeitliches F殲stengrab von Ihringen, Kreis Breisgau- Hochschwarzwald, Archaeologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Wuerttemberg 1993, Stuttgart 1994, 109-12, fig.61; Tre`sors Celtes et Gaulois, exhib. Colmar, 1996, colorpl.9.

21. L.K. Galanina, Glass Vessels from the Kurdjipsky Barrow, Archeologiceskji sbornik Gosudarstvennyi ordena Lenina Ermitage <=Asbor> 12, 1970, 44, no.11.

22. Philadelphia, Univ.of Pennsylvania Mus. D. Barag, An Unpublished Achemenid Cut Glass Bowl from Nippur, JGS 10, 1968, 17-20.

23. Oliver, op.cit. 1970. Goldstein, op.cit. 1979, nos.248, 251. A. von Saldern, Two Achaemenid Glass Bowls and a Hoard of Hellenistic Glass Vessels, JGS 17, 1975, 37-9. Geneva: Muse`e d'Art et d'Histoire (Inv.no. 14396). Catalog of Glass in the Hueseyin Kokabas ∨ Collection, Istanbul 1984, no.80, fig.30. Naples: G.D. Weinberg, Hellenistic Glass Vessels from the Athenian Agora, Hesperia 30, 1961, pl.93a. S. Baumgaertner, Glaeser, Antike… Museum der Stadt Regensburg, Karlsruhe 1977, no.1. N. Kunina, Ancient Glass in the Hermitage Collection, St. Petersburg 1997, no.47, colorpl.27. Grose, op.cit.1989, no.34. Sangiorgi: Saldern, op.cit.1959, fig.29. M. Pfrommer, Studien zu alexandrinischer und grossgriechischer Toreutik fruhhellenistischer Zeit, Berlin 1987, 251, no.KBk30 (Sotheby's London, July 12, 1976, no.307). Solid Liquid, Fortuna Fine Arts, New York 1999, no.1.

24. 類似したギリシア銀器とイラン銀器を様式的に区別することは時に容易なことではない。ギリシアの陶芸と金属工芸との関係も参照されたい。: B.B. Sefton, Persian Gold and Attic Black-glaze: Achaemenid Influences on Attic Pottery of the 5th and 4th Centuries B.C., Annales Arche`ologiques Arabes Syriennes 21, 1971 = Ixe`me Congre`s Internat. D'Arche`ologie Classique, Damascus 1969, 109-11.

25. Schmidt, op.cit. 1953, pl.31ff.

26. M.L. Trowbridge, Philological Studies in Ancient Glass (Univ. of Illinois Studies in Language and Literature ⅩⅢ, 3-4, 1928), Urbana 1930, 134, 151から引用

27. W. Schiering, Die Werkstatt des Pheidias in Olympia 2: Werkstattfunde (DAI Olympia Forsch. 18), Berlin 1991, 47-50, 131ff. 157ff.

ペルシャのはじまり

紀元前7世紀末から6世紀初頭にかけて、メソポタミアの最大の帝国アッシリアとその最大のライバル、ウラルトゥは、あいついで北西イランのメディアと南メソポタミアのバビロニアの同盟勢力のもとに降り、更にそのイラン系メディアは西アジア世界を初めて統一する大帝国となりました。

イラン系メディアは程なく東南イランの大きい同盟勢力であったイラン系ペルシャに取って替わられ、アケメネス朝ペルシャが立ちました。

紀元前8-7世紀のこの混沌とした時代を通じて、これらメディア、ペルシャなどのイラン民族は好戦的な神々を仰ぐ伝統的な宗教から、秩序と正義そして平和をもたらす世界の救世主をあおぐゾロアスター教に急速に転向して行きました。

彼らは世界を善悪の対立としてとらえ、最終的に善の勝利としての審判が到来するとする終末論から、現実の世界の変容を求めました。

それは絶対善の創造神アフラ・マズダーのもとに統一された世界、アフラ・マズダーから多くの者の中の唯一の王となされた王を頂く巨大帝国をつくりあげることであったと言えます。

Mary Boyce/ A History of Zoroastrianism/ Leiden I- 1996-172ff. , II- 1982- 105 ff.

ペンダント付トルク

宝飾品ー腕輪、トルク、イヤリング、首飾、指輪印章他

有翼獣文様鉢

鴨装飾ブレスレット

鴨装飾ブレスレット

馬形リュトン

帝王闘争文様鉢

二頭の馬浮彫

ライオングリフィン形リュトン

メディア人従者浮彫

帝都建設の銘文

――そして此は私がスサに建てた宮殿。その資材は遠方より齎された。地面を地中の岩盤まで深く掘り下げた。土を取り除くと砂利が敷き詰められ、あるところは40キュビットあるいは20キュビットに達した。宮殿はこの砂利の上に建てられたのである。地中深く掘り、砂利を敷き詰め、泥煉瓦を作る―――――これら全ての作業はバビロニア人が行った。 杉材はレバノンの山からアッシリア人がバビロンまで運び、カリア人イオニア人がスサまで運んだ。シッソ材はガンダーラとカルマニアから、ラピス・ラズリ、カーネリアンの準貴石はソグディアナから。トルコ石はホラズム、銀とエボニー材はエジプト、壁の装飾はイオニア、象牙はエチオピア(クシュ)やインドそしてアラコジア、石柱はエラムのアビラドゥから運ばれた。石職人はイオニア人、リディア人。金細工師、象嵌細工師はメディア人、エジプト人。バビロニア人は煉瓦を焼き、メディア人、エジプト人は壁を装飾した。 このスサにすばらしいものを建てんとし、すばらしいものができた。願わくばアフラマツダの神が私、父ウィスタシュパそして我が同胞をみそなわし賜わんことを。

Walter Hintz/ The Elamite Version of the Record of Darius's Palace at Susa / 1950 Journal of Near Eastern Studies Vol.IX No.1

ペンダント付トルク

宝飾品ー腕輪、トルク、イヤリング、首飾、指輪印章他

有翼獣文様鉢

鴨装飾ブレスレット

鴨装飾ブレスレット

馬形リュトン

帝王闘争文様鉢

有翼山羊装飾ブレスレット

獅子頭装飾ブレスレット

双獅子頭装飾ブレスレット

二頭の馬浮彫

ライオングリフィン形リュトン

メディア人従者浮彫

Catalogue Entry

Sizable glass vessels from the era before the advent of glassblowing (the first century B.C.) rarely survive intact in the ancient Near Eastern world. Fragments of fluted glass beakers or, conceivably, horn-shaped cups similar to this example were found in the excavations at Persepolis in southwestern Iran and are datable to the Achaemenid period (558-331 B.C.). On one small fragment vertical fluted lines terminate in what appears to be an animal's head.1

This remarkable molded and carved lion-headed beaker is made from a transparent soda-lime glass that appears to be greenish in color (as a result of iron impurities) only in the thickest part around the lion's head. The delicate and precious cup imitates the form of vessels of pre-Achaemenid and Achaemenid date (eighth-fifth century B.C.) hammered from gold and silver. Details of the head, particularly the indications of wrinkles and folds in the skin, are comparable to lion heads of the Achaemenid period, although the style of this rendering, as is often the case with works made of glass, differs slightly from Achaemenid images in stone, ceramic, and metal.

The cup, which was cleaned in modern times and is without the weathered iridescent surface commonly seen on ancient glass, is in remarkable condition. Damage is restricted to a stress crack that extends obliquely from the head of the animal part way down the fluted body. As a type of ancient Near Eastern luxury vessel not often preserved, this rare work of art is an example of a court drinking or pouring vessel that is better known in ceramic and metal.

POH

1. See Schmidt 1957, pp. 91-92, nos. 9, 10, pl. 67.

Catalogue Entry

Allegedly found in Iran, 5th?-first half 4th centuries B.C.

Clear glass with green tinge. Fused in a tripartite (?) mold or made in the lost-wax-process; after cooling the beaker was cut and engraved.

Broken in at least 2 parts and recently repaired, the break covered with dirt to mask the joint.

Strain crack extending from lion's head to fluted body. Point of the upper right tooth missing (ancient break). Slight iridescence and opaque tan-colored scum.

Height 17.1cm, Rim diam 10.5cm, weight 309gram

The relatively large vessel flares trumpet-like to a plain rim. Its body has carefully been cut to from 36 horizontal grooves or flutes. The lower portion is molded into a lion's head, with its mouth open. Details such as eyes, nose, nostrils and teeth are engraved with help of a rotating wheel.

This unique beaker (in form of a situla without handle) is a magnificent example of Achaemenid luxury glass at its best. The only other glass vessel comparable has been found in Persepolis (infra)1). In this case, however, it is a curved rhyton with an undecorated (?) body?|the central portion of the vessel is missing?|and a protome in form of a bull attacked by a lion. The quality of the cutting is quite superb, attesting to the high artistic and technical level of workmanship of the creator of this rhyton. Unfortunately it is undated but as Persepolis reached its peak in the 5th cent.?|the palace was begun about 518 by Darius and continued to be enlarged under Xerxes‡T(485-465) and Artaxerxes I (465-424)?|it is reasonable to assume that the workshops attached to the royal household in Persepolis, Susa and Ecbatana likewise were at their best particularly in the 5th cent. Below it will be shown that the finds of luxury glass from Iran during this time were not imports from Mesopotamia bur products of foreign artisans coming from the west?|I.e. perhaps from Assyria?|and of local, highly skilled workmen.

Achaemenid Glass

The history of clear luxury glass begins in Assyria in the 8th century B.C. Before this time vessels and inlays were made of opaque or translucent, highly colored glass in imitation of objects in other materials such as faience and stone. The core-formed perfume containers from Alalakh (northern Syria), Assur and Ur datable to the 15th and 14th century2) and of the 18th-dynasty in Egypt3) as well as the masses of inlays found in Egypt and at places such as Dur Kurigalzu?|Aqar Quf (near Baghdad) give testimony to the preference of polychrome glass in early times. Likewise multicolored mosaic glass was made during the same period in Egypt and in Mesopotamia4).

No less than seven centuries passed before efforts were made to produce a clear or almost clear glass in imitation of the rare rock crystal. Technologically this new material was not easy to produce as it involved the search for agents to decolorize the glass. This seems to have been achieved first in Nimrud around the turn from the 8th to the 7th century B.C. An alabastron with particularly thick walls preserved in the British Museum bears an inscription in cuneiform "Palace of Sargon" and "King of Assyria", indicating that it belonged to the household of King Sargon II (722-705)5). The Vessel is greenish and translucent due to its compactness, with walls 0.7-1.7 cm thick. Also a vase, several hemispherical bowls and fragments of about 100-140 additional bowls were discovered in Nimrud of which quite a few, of thinner-walled glass, are almost colorless. Among the sherds excavated in the 50's and 60's of the last century a few meticulously engraved and cut fragments of clear glass represent Assyrian luxury of the late 8th and 7th centuries at a very high level. One of the products of this or a similarly equipped workshop is an almost clear mesomphalic bowl of the last quarter of the 8th century found in a girl's tumulus-grave at Gordion in Turkey6).

The glass from Nimrud and Gordion does not stand alone. Hemispherical bowls found in Bologna, Praeneste and Fortetsa-Knossos, a shallow bowl from Babylon, a jug from the Aliseda treasury in Spain and an amphora from the Giardino Margherita in Bologna all seem to date from the 7th century and may have been made in Assyria and, in some cases?|for example the Aliseda-jug?|in Phoenicia. A series of slender alabastra of 6th/5th century date with thick walls and greenish or grayish tint should be added to this corpus of early glasses "in the new style."

The glasses of practically decolorized material found or said to have been found in Iran are the successors of this early group. They, in turn, seem to have initiated the making of clear or almost clear glass in the Aegean and greatly influenced the production of multiformed Hellenistic glass.

The most important finds of Achaemenid glass come from Persepolis, a site investigated by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in 1931 and 1934. Others have come to light at places as diverse as Ephesus, Aslaia (Cyrenaica) and Ihringen (South-West Germany), Nippur, Kurdshipskij Kurgan and Trialeti (South Russia). In addition, several important pieces have been supplied by the antiquities market. Among the vessels types the bowl?|in a few variants?|is the most common form in Achaemenid glass. All finds either excavated under professional supervision or purchased by private collections and museums form a more or less homogenous group of objects among which the Shumei beaker ranks as one of the finest known.

The treasury in Persepolis revealed a host of fragmentary glasses of highest quality made almost entirely of "water-clear" glass that had been extensively cut7). All of them were fused in molds, vessels as well as decorative objects that may have served as ornaments or inlays. Among the finds are the remains of about 20 vessels. Particularly noteworthy are a bowl with deeply lobbed, almond-shaped bulges and several vertically fluted beakers, a decorative device identical to the decoration on the Shumei beaker. Other sherds include handles of jugs or vases and an expertly engraved vessel of thick glass. Some of the small ornaments are beautifully engraved, testimony to the admirable standard of workmanship at the royal ateliers.

In 1959 a spectacular and unique rhyton of almost clear glass with the protome in form of a bull attacked by a lion was found by Ali Sami (Univ. of Shiraz) in Persepolis at the base of the Rahmat mountain. Although discovered at a depth of about 5 meters in an undatable level it certainly belongs to the series of glasses from the Persepolis treasury. Both the rhyton and the Shumei beaker as well as the other vessels are based on prototypes in precious metal and stone. The beaker in the Shumei collection could, for example, be compared with similarly shaped Mannaian silver rhyta of an earlier period in Iran (south of Lake Urmia), namely the 7th century8). Also rhyta of precious metal such as those from the kurgans of the Seven Brothers in south Russia or one of the 1st half of the 5th century formerly in the Schimmel collection and now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York feature horizontally fluted bodies with flaring rim and protome in shape of rams9).

The decorative device of covering a vessel-surface with grooves or flutes was not limited to rhyta and beakers of the Shumei variety. A fragmentary beaker of clear glass with horizontally arranged grooves below a band of lotus blossoms in high relief was found in grave B in Derveni, north of Thessaloniki (Salonika). Although dated "after 323/315" it may be a treasured piece of late Achaemenid workmanship as it is closely related to the fluted beakers found at Persepoli (supra). Objects of this kind are faithful copies of Achaemenid silver beakers attested by examples in Berlin and Oxford10). The body of a glass vase (or rhyton ?) in Corning with egg-shaped body and wide neck flaring upwards is covered with pattern of vertical flutes11). Datable to the 5th century it imitates forms in metal example of which, an amphora with ibex handles found in Iraq, also dates from the 5th century12).

As already mentioned the bowl in Achaemenid times was the most popular form in metal and in glass. A number of well-dated glass bowls are helpful to put the Shumei beaker in its proper, historical context. Most of them are decorated either with flutes or with leaves radiating from a circlet at the center. They come in several variants?|either shallow or relatively deeply bodies?|and are always patterned after models in precious metal13). In our context only those objects will be mentioned that have been excavated under scientific supervision. Practically all of them are made of clear glass; those few of pale blue material are the exception14).

Among the oldest, safely dated objects known to me is a deep bowl with fluted body and everted rim found in a stone-built tomb in Aslaia, Cyrenaica, north-east of Benghazi15). Greek pottery found with it place the burial in the late 5th century. A fragmentary bowl of almost identical shape with leaves radiating from the center was discovered in a stone tomb in Sairkhe on the river Kvirila?|ancient Phasis?|in western Georgia. According to the other objects found in the tomb it can safely be put in the mid-5th century16). Similar bowls are known to come from Aineia and Veroia in Macedonia17) and from Rhodes18). Although they belong to graves of the last quarter of the 4th century and seem to be of Greek manufacture they are literal copies of earlier models of Achaemenid time.

Well known in the literature is a petalled bowl with everted rim found by D.G. Hogarth in the fill of the Artemision in Ephesus that was burnt in 356 B.C. Comparable to similar pieces of the 5th century it can be dated to the late 5th or 1st half of the 4th century19). Of undoubtedly mid-5th century date, however, is a shallow, undecorated bowl of clear glass that comes from a region far-away from the rest of the group, namely from a grave in Ihringen in south-west Germany20).

Closer to the "motherland" of Achaemenid glass manufacture are finds from locations in South Russia, Georgia and Nippur. Two bowls of a form similar to the piece from Ephesus come from the Kurdshipskij kurgan (south of Maikop), datable to the 4th century and from a tomb near Trialeti on the Algeti river, south-west of Tbilisi-Tiflis that has been assigned to the late 6th or 5th century21). Finally a deep, fragmentary bowl?|unfortunately unstratified?|with a pattern of overlapping leaves was discovered in Nippur in 188922).

Quite a few pieces are known that can be compared with the Achaemenid glass bowls mentioned in the foregoing. Some of them have long been part of museum holdings, others have entered public and private collections via the antiquities' market. They are preserved, for example, in Cologne, Corning, Dusseldorf, Geneva, Hamburg, Istanbul, Jerusalem, London, Munich, Naples, New York, Regensburg, St. Petersburg and Toledo; one was formerly in the Sangiorgi Collection (Rome), a few more are or were on the market23).

Conclusion

The group of similarly decorated glasses manufactured in molds of decolorized?|very rarely of pale blue?|material originates, as far as we know, from workshops established near royal residences in Achaemenid Iran. Although many finds come from locations far apart?| from Nippur to Germany?|the bulk has been excavated in Iran, namely in Persepolis where the finest pieces have come to light. In addition, vessels of precious metal that are known or said to be of Iranian workmanship served in practically every case as direct models for vessels of glass24). Their representations in stone appear in mass on the reliefs of the Apadana in Persepolis25).

The literary analogy in Iranian glass bowls is contained in Aristophanes' "Acharnians" (37,5) first put on stage in Athens in 425 B.C. where it is reported that Athenian ambassadors at the Persian court at Ecbatana "drank sweet wine from vessels of gold and glass26)." It can even be assumed that the beginning of the manufacture of more or less decolorized glass was formed in molds to serve as inlays for the gigantic gold-ivory statue of Zeus; these were discovered in Phidias' workshop in Olympia datable to about 435-425 B.C.27)

The influence of the Iranian luxury glass?|manufacturing facilities have not as yet been discovered?|is strongly felt in Hellenistic glass The vessels in this very prominent group make their first appearance in the last quarter of the 4th century in the Aegean in regions and locations such as Macedonia, Rhodes and Delos where they seem to have been made locally. At that time, however, it is not always possible to separate late Achaemenid from early Hellenistic works. Slightly later Hellenistic luxury glass probably of Alexandrian manufacture is found among the contents of richly appointed graves in southern Italy: the hoards from Canosa and Taranto are among the most famous finds of Hellenistic glass.

All vessels in this Hellenistic group owe their forms, their technology and partly their decorative motifs to Iranian prototypes as Iranian glass, in turn, had profited from the technological advances made in Assyria in the late 8th and 7th centuries. The glass from Persepolis and other locations and the many vessels closely related to this group?|such as the Shumei beaker?|constitute a corpus of Iranian luxury ware of the highest order. In the entire history of ancient glass not many periods have reached a comparable level of aesthetic excellence and superior workmanship.

Dr. Axel von Saldern

Ex-Director of the Museum of Art and Applied Arts in Hamburg, Germany

Notes:

01. Height 15 cm. Tehran, Iran Bastan Museum. Av. Saldern, Glasrhyta, Festschrift f?r Waldemar Haberey, Mainz 1976, 121-3, pl.32:1; S. Fukai, Persian Glass, New York-Tokyo-Kyoto 1977. Fig.8.

02. D.Barag, in: A.L. Oppenheim et al., Glass and Glassmaking in Ancient Mesopotamia, Corning 1970, 129-99.

03. B. Nolte, Die Glasgefaesse im alten Aegypten, Berlin 1968.

04. A.von Saldern, Mosaic Glass from Hasanlu, Marlik, and Tell al-Rimah, Journal of Glass Studies (=JGS) 8, 1966, 9-25; idem, Other Mesopotamian Glass Vessels (1500-600 B.C.), op.cit. Oppenheim et al. 1970,203-28; Nolte, op.cit. 1968.

05. D. Barag, Western Asiatic Glass in the British Museum, London 1985, no.26.

06. A.von Saldern, Glass Finds at Gordion, JGS 1, 1959, 22-7, figs.1-2.

07. E.F. Schmidt, Persepolis (OIP 68), Chicago 1953, pl.41; idem (OIP 69), Chicago 1957, 91-3, 127-32, pl.66-7.

08. C.K. Wilkinson, Two Ancient Silver Vessels, Bull. Metrop. Mus. Of Art 15, Summer 1956, 9-15; The Pomerance Collection of Ancient Art, The Brooklyn Museum 1966, no.54.

09. H. Hoffmann, The Persian Origin of the Attic Rhyta, Antike Welt 4, 1961, 21-9, pl.11 (rhyta from the Seven Brothers group of kurgans); Ancient Art. The Norbert Schimmel Collection (ed. By O. White Muscarella), Mainz 1974, no. 155. Cf. also Achaemenid vessels of gold and silver mainly of the 5th century featuring animal protomes and fluted bodies in: 7000 ans d'art en Iran, exhib. Paris 1962, nos.638ff.,pls.53ff.; Traci. Arte e cultura nelle terre di Bulgaria…, exhib. Venice 1989, nos. 138ff.

10. G. Hafner, Kretisch-Mykenisches in der sp?teren griechischen Kunst,

Festschrift des R?misch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 3, 1953, pl.6:6; A. Oliver, Jr., Persian Export Glass, JGS 12, 1970, fig.10.

11. S. Goldstein, Pre-Roman and Early Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning 1979, no.250.

12. Pomerance Collection op.cit. 1966, no.59.

13. Oliver op.cit. 1970; D.F. Grose, Early Ancient Glass, The Toledo Museum of art, New York 1989, 80-1, fig.48.

14. Vessel handle from Persepolis: Schmidt, op.cit. 1957, pl.67:1; bowl with leaf petals in Corning, Goldstein, op.cit. 1979, no.251.

15. M. Vickers, An Achaemenid Glass Bowl in a Dated Context, JGS 14, 1972, 15-6.

16. George Makharadze, Mariam Saginashvili, An Achaemenian Glass Bowl from Sairkhe, Georgia, JGS 41, 1999, 11-7.

17.. I. Vokotopoulou, Oi taphikoi toumboi tes Aineias, Athens 1990, 61, no.15 (tumulus ‡V, grave A); G. Touratsoglou, To xeiphos tes Veroia: symbole ste Makedonike oplopoia ton isteron klassikon xronon, Archaia Makedonia 4, 1986, 641-3, fig.5.

18. P. Triantafyllidis, New Evidence of the Glass Manufacture in Classical and Hellenistic Rhodes, Annales du 14e Congre's de 1'Association Internationale du Verre 1998 (2000), 30-1 fig.5-7.

19. Barag, op.cit. 1985, no.46.

20. R. Dehn, Ein sp?thallstattzeitliches Fyrstengrab von Ihringen, Kreis Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald, Archaeologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Wuerttemberg 1993, Stuttgart 1994, 109-12, fig.61; Tre'sors Celtes et Gaulois, exhib. Colmar, 1996, colorpl.9.

21. L.K. Galanina, Glass Vessels from the Kurdjipsky Barrow, Archeologiceskji sbornik Gosudarstvennyi ordena Lenina Ermitage <=Asbor> 12, 1970, 44, no.11.

22. Philadelphia, Univ.of Pennsylvania Mus. D. Barag, An Unpublished Achemenid Cut Glass Bowl from Nippur, JGS 10, 1968, 17-20.

23. Oliver, op.cit. 1970. Goldstein, op.cit. 1979, nos.248, 251. A. von Saldern, Two Achaemenid Glass Bowls and a Hoard of Hellenistic Glass Vessels, JGS 17, 1975, 37-9. Geneva: Muse'e d'Art et d'Histoire (Inv.no. 14396). Catalog of Glass in the Hueseyin Kokabas?E Collection, Istanbul 1984, no.80, fig.30. Naples: G.D. Weinberg, Hellenistic Glass Vessels from the Athenian Agora, Hesperia 30, 1961, pl.93a. S. Baumgaertner, Glaeser, Antike… Museum der Stadt Regensburg, Karlsruhe 1977, no. 1.N. Kunina, Ancient Glass in the Hermitage Collection, St. Petersburg 1997, no.47, colorpl.27. Grose, op.cit.1989, no.34. Sangiorgi: Saldern, op.cit.1959, fig.29. M. Pfrommer, Studien zu alexandrinischer und grossgriechischer Toreutik fr?hhellenistischer Zeit, Berlin 1987, 251, no.KBk30 (Sotheby's London, July 12, 1976, no.307). Solid Liquid, Fortuna Fine Arts, New York 1999, no.1.

24. It should be pointed out that it is sometimes not easy to sort out stylistically similar Iranian from Greek silverware. - Cf. also the relation of Greek ceramics to toreutic art: B.B. Sefton, Persian Gold and Attic Black-glaze:Achaemenid Influences on Attic Pottery of the 5th and 4th Centuries B.C., Annales Arche'ologiques Arabes Syriennes 21, 1971 = Ixe'me Congre's Internat. D'Arche'ologie Classique, Damascus 1969, 109-11.

25. Schmidt, op.cit. 1953, pl.31ff.

26. Text in: M.L. Trowbridge, Philological Studies in Ancient Glass (Univ. of Illinois Studies in Language and Literature ‡]‡V, 3-4, 1928), Urbana 1930, 134, 151.

27. W. Schiering, Die Werkstatt des Pheidias in Olympia 2: Werkstattfunde (DAI Olympia Forsch. 18), Berlin 1991, 47-50, 131ff. 157ff.