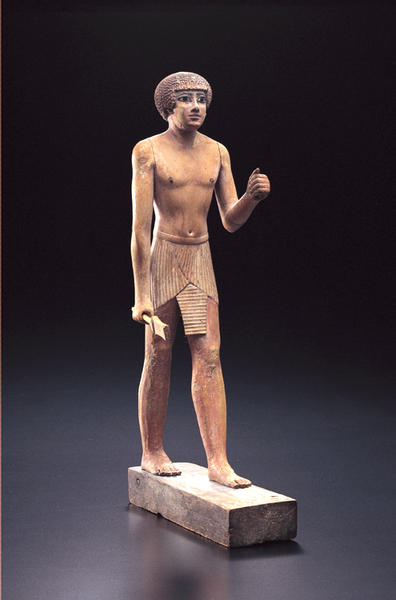

ウェパイ像

- エジプト

- エジプト中王国第12王朝時代

- 前1900-前1840年頃

- 木に着彩

- H-34.1

どこに祀られたか

古代エジプトの墓(マスタバ)の構造は、死者を葬った地下の玄室から地上まで小さな穴が開けられ、地上の部分は石でこれを塞いだものでしたが、この地上の構築物は「kaの家」と呼ばれました。

このkaの家の礼拝所の奥の閉ざされた部屋(serdab)にka像が置かれました。

この部屋の扉は実際には開かず「偽扉」と呼ばれていますが、しばしばその上部には小さな窓が開けられ、それを通して遺族は「ka」を拝むことができました。

中王国(前21-17世紀)のテキストによると「ka」は、マスタバのみならず個人の家の神殿、もしくは屋根裏の礼拝所、そして庭にも置かれ、拝まれたと言われています。

ナクト像

なぜ作られたのか

この像はおよそ四千年の歳月を経ていますが、風化の感じられない、まだその木の香も残っていそうな木彫像です。

この木彫像はカァ(ka)像と呼ばれています。エジプトでは一人の人間が生まれる時kaもその「二重身」として生まれ、死後もそれは生き続け供養を必要としたのです。それは個人を生かす活力を与えるものと考えられていたようです。

通常、墓の地下にはその人の遺体を葬ったのですが、そのkaを象った像を遺族は地上のチャペルの奥に祀り、供物を捧げました。事情の許さない時はそのチャペルの内壁に浅浮彫等で描かれた供物が代用として考えられたのです。

ka像は墓のみに収められたのではなく、しばしば家にも祭られたと言われていますが、特にこの像が造られた第十二王朝頃よりkaに対する供養は日々あるいは定期的になされるようになりました。

後世の文献資料から考えて、それはある意味で霊界の主神オシリスの審判における守護霊と見做されるようになったのであると言われています。

ナクト像

死者の書のka

「我がheart,我がmother --審判にあってはなにものも我に抗するものなきよう-- 汝は我がka 我がうちにありて四肢を強くせし-- 我が進むべき至福の庭に先立ちて導かれんことを-- Shenit(冥界の神的存在の一つ)が神の御前で我が名に汚れを着せず、我に抗がう偽りを言いたてることなきよう。--」

Book of the Dead XXXB

このように新王国(16th-11thC.B.C.)頃の「死者の書」によれば、[我を産み出せしBreast]とも呼ばれるkaに対し審判において味方をするよう懇願しています。

これはkaが何か、個人とは独立した一種の規律のようなものと見做されていたことを示していると考えられます。

かつては天国は神々と王のみに許されていましたが、中王国時代頃より官僚(神官)や身分の高い人々にもそれは開かれるようになり、彼等の通過しなければならない審判の重要性が目立ってきたものと考えられます。

ナクト像

Catalogue Entry

The arid climate of Egypt's deserts has preserved many wooden objects in near pristine condition. Statues and statuettes of painted wood were originally part of burial equipment for persons of high rank, and were believed to provide repositories for the soul of the deceased. Some of these sculptures were deposited near or inside the coffin; others stood in niches or against the wall of a cult chamber, surrounded by funerary objects, such as models of boats, workshops, or granaries, and clay vessels.1

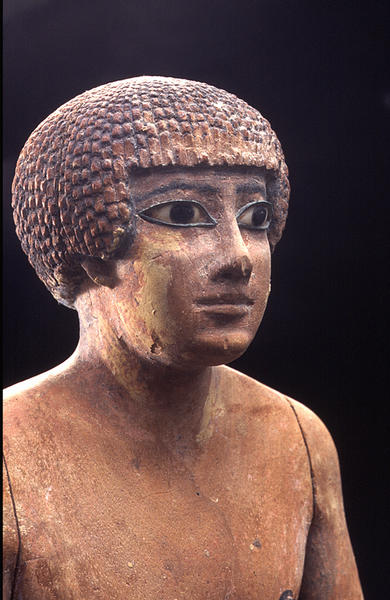

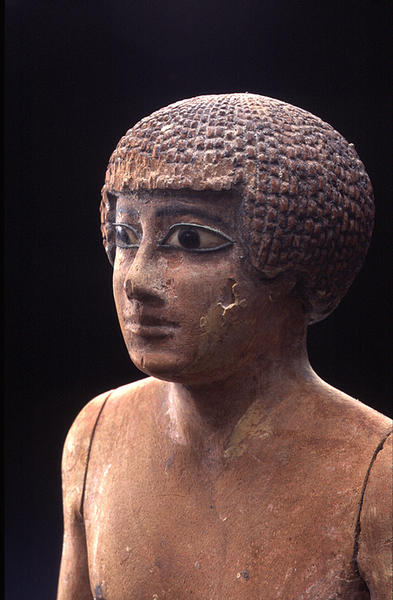

Egyptian statues are usually idealized images showing men and women as beautiful and eternally youthful. Identification with particular persons was provided by inscriptions. The inscription on the base of this statuette reads: "The revered Wepay." The term revered indicated that all proper funerary rites had been performed for the man Wepay--a name especially common in the ancient province of Asyut in Middle Egypt.2 Ancient Asyut was an important wood-carving center during the late third and early second millennium B.C.; wooden statues and statuettes found in tombs at the site are now in the collections of major museums.3 Many of these works represent a tomb owner in the posture and costume of this statuette. The short pleated kilt, with its wedge-shaped front part, initially a royal garment, was commonly depicted as the costume of high-ranking officials by the time Wepay's statuette was carved.

Like other Egyptian wooden statues, the figure of Wepay is made up of many pieces of wood (fourteen in this case). Both legs, the neck, and the cheeks are covered with thick layers of gesso, and the entire figure was painted. The nipples were once inlaid with wood. The official wears a round ceremonial wig composed of vertical rows of small curls in an interlocking pattern.4 Indentations on each side of the wig serve to free the lower part of the ear.5 The curls above the forehead are now abraded. Originally, the protruding wig would have created deep shadows in the corners above the eyes, which are inlaid with Egyptian alabaster and obsidian in copper sockets. In his left hand Wepay carried a long walking stick (now missing), a sign of dignity, while his right hand grasps the handle of a scepter, a token of power and rank conferred by the Egyptian pharaoh on courtiers and state officials.

Stylistically, the Wepay statuette belongs among the later extant Asyut wood carvings, and most probably dates from the reign of Senwosret III (about 1878-1859 B.C.). The serene expression of the face, with its straight mouth and softly rounded lips, and the delicate modeling of the torso musculature, especially around the navel and waist, are characteristic of mid-Twelfth Dynasty art.6 At this time, Egyptian artists had left behind the vigorous and somewhat archaic images of the First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom (about 2100-1900 B.C.) and were creating evenly proportioned figures with somber facial expressions and a refinement in surface treatment rarely paralleled in Egyptian art of any other period.7

DA

l. See Chassinat and Palanque 1911, pp. 31-32, 47, fig. 3, pl. 34.

2. See Ranke 1935, p. 78, nos. 13, 14; Franke 1984, p. 152, dossier 203.

3. These include Egyptian Museum, Cairo: see Chassinat and Palanque 1911, pls. 5, 36; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: see Smith 1981, p. 156, fig. 148; Mus馥 du Louvre, Paris: see Delange 1987, pp. 76-77, 15l-61; and Museo Egizio, Turin: see Donadoni Roveri 1988, p. 103, fig. 136; Donadoni Roveri 1989, p. 100, fig. 153, p. 130, fig. 206.

4. An arrangement of curls in horizontal rows conforms to Old Kingdom traditions and is also common among the wooden figures from Asyut (see note 3). Vertical strands are seen on the sandstone statue of Intef (see Saleh and Sourouzian 1987, no. 70) or on such wooden figures as the one in Baltimore (see Steindorff 1946, p. 35, no. 78, pl. 14) or in Cairo (see Borchardt 1911, pp. 146-47, no. 220, pl. 45).

5. There were two versions of this wig. In one the whole ear is visible (see Borchardt 1925, p. 55, no. 464, pl. 77; Legrain 1906, pp. 3-4, no. 42004, pl. 2; Hayes 1953, p. 206, fig. 123); in the other, predominantly favored by Asyut artists, only the lower parts of the ears are free, while the wig ends either with a straight edge or a curved indentation above the ears (see Chassinat and Palanque 1911, pls. 5, 34, 36; Delange 1987, pp. 76-77).

6. Compare, for the torso, the hard-stone statues of King Senwosret III (see Evers 1929, pls. 77, 80, 82), and for the torso and face, the wooden statuettes in Baltimore (see Steindorff 1946, p. 35, no. 77, pl. 14) and in Paris (see Delange 1987, pp. 206-7). A straight mouth is depicted on statues from as early as the reign of Amenemhat II (about 1918-1884 B.C.); see Evers 1929, pl. 69. However, on works of that period the torso musculature is different from Wepay's, as can be seen both on wood and stone statuettes (see Hayes 1953, p. 192, fig. 117, p. 211, fig. 128); The wooden statuette is dated on the basis of archaeological evidence to the reign of Amenemhat II or of Senwosret II--between about 1918 and about 1878 B.C.

7. The round wig (see note 5 above) hitherto has been understood as a typical feature of the early Twelfth and the Thirteenth Dynasty (see Bourriau 1988, p. 71). However, the mid-Twelfth Dynasty characteristics of the Wepay statuette are unmistakable, thereby attesting to the continuation of this type of wig into the reign of Senwosret III.