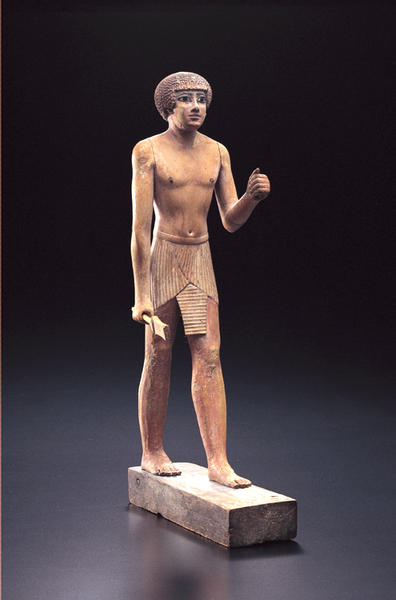

Statuette of Wepay

- Egypt

- Egypt, Dynasty 12

- 1900 - 1840 B.C.

- Painted wood

- H-34.1

- probably from Asyut

Catalogue Entry

The arid climate of Egypt's deserts has preserved many wooden objects in near pristine condition. Statues and statuettes of painted wood were originally part of burial equipment for persons of high rank, and were believed to provide repositories for the soul of the deceased. Some of these sculptures were deposited near or inside the coffin; others stood in niches or against the wall of a cult chamber, surrounded by funerary objects, such as models of boats, workshops, or granaries, and clay vessels.1

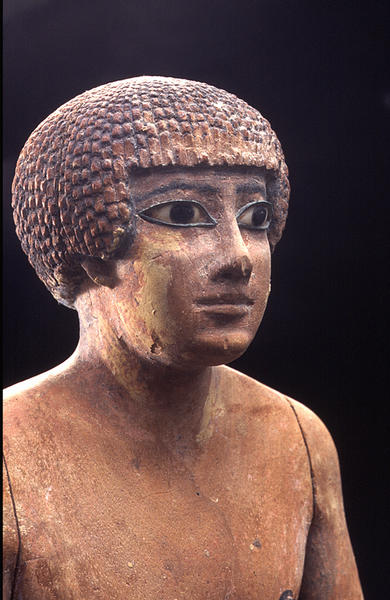

Egyptian statues are usually idealized images showing men and women as beautiful and eternally youthful. Identification with particular persons was provided by inscriptions. The inscription on the base of this statuette reads: "The revered Wepay." The term revered indicated that all proper funerary rites had been performed for the man Wepay--a name especially common in the ancient province of Asyut in Middle Egypt.2 Ancient Asyut was an important wood-carving center during the late third and early second millennium B.C.; wooden statues and statuettes found in tombs at the site are now in the collections of major museums.3 Many of these works represent a tomb owner in the posture and costume of this statuette. The short pleated kilt, with its wedge-shaped front part, initially a royal garment, was commonly depicted as the costume of high-ranking officials by the time Wepay's statuette was carved.

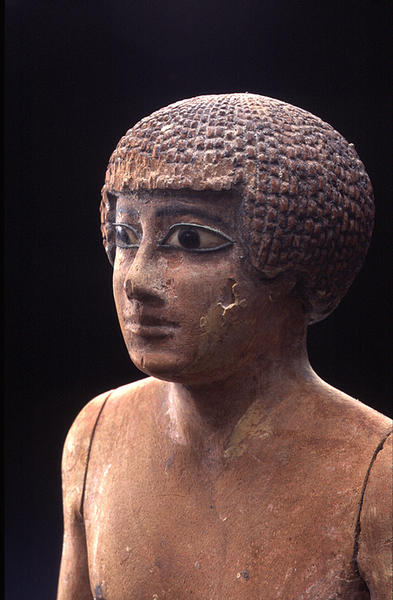

Like other Egyptian wooden statues, the figure of Wepay is made up of many pieces of wood (fourteen in this case). Both legs, the neck, and the cheeks are covered with thick layers of gesso, and the entire figure was painted. The nipples were once inlaid with wood. The official wears a round ceremonial wig composed of vertical rows of small curls in an interlocking pattern.4 Indentations on each side of the wig serve to free the lower part of the ear.5 The curls above the forehead are now abraded. Originally, the protruding wig would have created deep shadows in the corners above the eyes, which are inlaid with Egyptian alabaster and obsidian in copper sockets. In his left hand Wepay carried a long walking stick (now missing), a sign of dignity, while his right hand grasps the handle of a scepter, a token of power and rank conferred by the Egyptian pharaoh on courtiers and state officials.

Stylistically, the Wepay statuette belongs among the later extant Asyut wood carvings, and most probably dates from the reign of Senwosret III (about 1878-1859 B.C.). The serene expression of the face, with its straight mouth and softly rounded lips, and the delicate modeling of the torso musculature, especially around the navel and waist, are characteristic of mid-Twelfth Dynasty art.6 At this time, Egyptian artists had left behind the vigorous and somewhat archaic images of the First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom (about 2100-1900 B.C.) and were creating evenly proportioned figures with somber facial expressions and a refinement in surface treatment rarely paralleled in Egyptian art of any other period.7

DA

l. See Chassinat and Palanque 1911, pp. 31-32, 47, fig. 3, pl. 34.

2. See Ranke 1935, p. 78, nos. 13, 14; Franke 1984, p. 152, dossier 203.

3. These include Egyptian Museum, Cairo: see Chassinat and Palanque 1911, pls. 5, 36; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: see Smith 1981, p. 156, fig. 148; Mus馥 du Louvre, Paris: see Delange 1987, pp. 76-77, 15l-61; and Museo Egizio, Turin: see Donadoni Roveri 1988, p. 103, fig. 136; Donadoni Roveri 1989, p. 100, fig. 153, p. 130, fig. 206.

4. An arrangement of curls in horizontal rows conforms to Old Kingdom traditions and is also common among the wooden figures from Asyut (see note 3). Vertical strands are seen on the sandstone statue of Intef (see Saleh and Sourouzian 1987, no. 70) or on such wooden figures as the one in Baltimore (see Steindorff 1946, p. 35, no. 78, pl. 14) or in Cairo (see Borchardt 1911, pp. 146-47, no. 220, pl. 45).

5. There were two versions of this wig. In one the whole ear is visible (see Borchardt 1925, p. 55, no. 464, pl. 77; Legrain 1906, pp. 3-4, no. 42004, pl. 2; Hayes 1953, p. 206, fig. 123); in the other, predominantly favored by Asyut artists, only the lower parts of the ears are free, while the wig ends either with a straight edge or a curved indentation above the ears (see Chassinat and Palanque 1911, pls. 5, 34, 36; Delange 1987, pp. 76-77).

6. Compare, for the torso, the hard-stone statues of King Senwosret III (see Evers 1929, pls. 77, 80, 82), and for the torso and face, the wooden statuettes in Baltimore (see Steindorff 1946, p. 35, no. 77, pl. 14) and in Paris (see Delange 1987, pp. 206-7). A straight mouth is depicted on statues from as early as the reign of Amenemhat II (about 1918-1884 B.C.); see Evers 1929, pl. 69. However, on works of that period the torso musculature is different from Wepay's, as can be seen both on wood and stone statuettes (see Hayes 1953, p. 192, fig. 117, p. 211, fig. 128); The wooden statuette is dated on the basis of archaeological evidence to the reign of Amenemhat II or of Senwosret II--between about 1918 and about 1878 B.C.

7. The round wig (see note 5 above) hitherto has been understood as a typical feature of the early Twelfth and the Thirteenth Dynasty (see Bourriau 1988, p. 71). However, the mid-Twelfth Dynasty characteristics of the Wepay statuette are unmistakable, thereby attesting to the continuation of this type of wig into the reign of Senwosret III.