隼頭神像

- エジプト

- エジプト第25王朝後期-第26王朝時代

- 前690-前525年頃

- 青銅

- H-69.5 D-35 W-18.5

この彫像は隼の頭に人間の耳と男性の体を持つ神を表し、上下エジプトの二重冠をかぶっている。銀箔と周りを金箔で象眼された目も人間のようである。玉座の側面には上エジプトと下エジプトの植物紋章である百合とパピルスが結び付けられたデザインで構成され、この「二つの土地の統一」を象徴している。それはこの像がかぶる二重冠も同様の意味がある。

神殿の奉納像について

神殿の奉献の部屋は最奥部の至聖所より1以上室程隔たった前室にあたり、大小の青銅の奉納像に加え、小さな陶製やフェイアンス製の小像の類もつめこまれ、それが限度を越えるとそれらは神殿内から取り出され、境内の大きな穴に埋蔵されました。

多くのそのような場所が見つかっていますが、1903年にカルナック神殿の境内で17000ものブロンズ小像と751の大きな像といった大量の奉納像が発掘されています。

獅子頭神像

なぜ奉納されたのか

永遠の至福を求めるエジプト人は、更に個人的に神像を造立し神殿に奉納しました。

これらの像の足元には奉納者の名前が刻まれていましたが、これは奉納者のkaがその名前とともにそこに生きていると考えられたのです。

これらは神殿内部に収められることによって、奉納者がその名前を不朽のものとし、死後も神に捧げられた供物と祭祀に与り、永遠の至福を享受する事を願ったものだったのです。

獅子頭神像

隼の頭部を持った神像について

この隼の頭部を持った神像は上下のエジプトを統一して支配する王の象徴である二重王冠を頂いています。

これは王を象徴するホルス(Horus)神をかたどったものです。エジプトの王は太陽神ラァ(Ra)の息子であるとされ、同じくラァの息子であるホルス神と同一視されました。

ラァもホルスも通常隼の姿に表現されましたが、エジプト人にとって天空を翔け太陽に溶け込んで一体となるかに見える隼は正に太陽神の象徴であったのです。

玉座の文様について

このホルスの奉納像は、その奉納者の名前が台座に刻まれていたと思われます。

それは通常足先の置かれている台の前面や側面に刻まれたのですが、この像は腐食が激しく文字の痕跡さえも見られません。

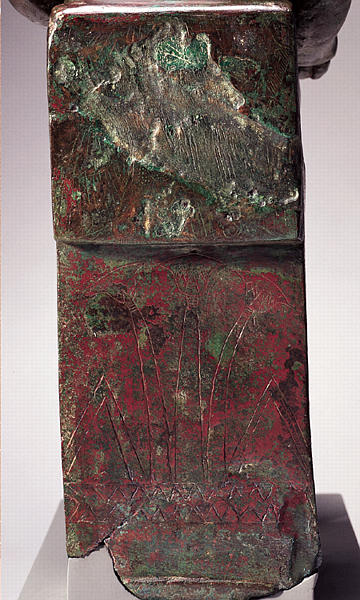

玉座の側面は多くの像に見られるように、鱗文様に、長方形で囲まれた上下エジプトの統一を象徴する文様が組み合わされています。

玉座の意匠

玉座の側面に彫られているのは、羽文様と上下エジプトの統合を象徴する「セマタウイ」という意匠である。これは、気管に接続した二つの肺をかたちどったものの周りに、上エジプト下エジプトを示す植物紋章の百合とパピルスが結び付けられるデザインで構成されている。「二つの土地の統一」すなわちエジプトの二つの伝統的地域の統一を象徴している。第4王朝以降、この標章は王の全土統一支配を強調するものとなり、王の玉座の側面によく表された。この像の玉座背面には水の流れから生えているパピルスの茂みが見られ、おそらく幼児期のホルスが、その母イシスに育てられたパピルスの生い茂る湿地の暗喩であろう。玉座に表された主題を総合すると、オシリスとイシスの息子として、また統合されたエジプトの支配者たる王の聖なる化身として、この像がホルスである可能性は高くなる。

Catalogue Entry

This imposing sculpture depicts a falcon-headed deity, seated upon a cuboidal throne and wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.1 It is linked by its size, technique, and iconography to a series of large bronze images discussed in the preceding entry (cat. no. 7). Presumably one of a variety of forms of the falcon god Horus, the image has human ears and a well-defined male torso.2 The treatment of the figure, with a depression forming a bipartite division of the chest descending to a drop-shaped hollow at the navel, a slim waist, and button-like nipples, is very similar to depictions of royal figures from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, such as the figure of Psamtik I, now in the Brooklyn Museum.3

This bronze figure presents several technical details worthy of mention. The double-crown headdress has been cast separately, is hollow, and is currently attached to the head with lead solder. A tang with square cross-section that extends upward from the top of the head was originally used to secure the crown to the head of the figure.4 Most Late Period Egyptian bronzes are cast in one piece, or, if the crown is designed to be attached to the figure, it is secured with a tenon that fits into a cavity in the head of the deity.5 The eyes are inlaid with sheets of silver and encircled with an inlaid gold rim, formed to the shape of a human eye. A casting gate or support has been left in place between the proper left hand and the left knee, a detail present on several other large-scale Egyptian bronzes from this period, such as two examples now in the Sackler Museum, Harvard.6

The sides of the throne (fig. 1) have been engraved with a pattern of feathers and a sema-tawy motif. This element, formed of the heraldic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt, the lily and papyrus, tied around an anatomical unit of two lungs attached to the trachea, symbolizes the "union of the two lands," the unification of the two traditional sections of Egypt. From the Fourth Dynasty onward, this emblem underscored the king's uniting rule and was often depicted on the sides of royal thrones. The back of this throne shows a papyrus thicket emerging from a watercourse, probably an allusion to the papyrus marsh where the infant Horus was reared by his mother, Isis. The sum of the motifs depicted on the throne aid in the identification of Horus as the son of Osiris and Isis, and heavenly personification of the king, who is the ruler of united Egypt. This imagery is echoed by the headdress worn by the bronze figure, the double crown of a unified Egypt.

The image of a falcon-headed deity wearing the double crown, shown seated, standing, or grouped in combination with other deities, is known from a number of other examples.7 The closest comparison can be found in a seated bronze figure from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty capital at Sais that is now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.8 As in the Shumei example, that figure is seated on a cuboidal throne. The sides of the throne are engraved with another pair of rare examples of a royal offering scenes. In this case, the cartouche of King Psamtik I (r. 664-610) states that the royal figure is presenting before Horus of Pe (Buto) and the lion-headed goddess Wadjet. In addition, an inscription on the base of the statue itself identifies the figure as "Horus of Pe."9 Thus, this Shumei falcon-headed figure, like the other large bronze in the collection (cat. no. 7), is associated the image of Horus as localized in Pe (Buto), but rather than the lion-headed Horus, son of Wadjet, we have the hawk-headed Horus, representative of the king, unifier of the two lands.

NT

1. Acquired in Cairo in 1935, by Dr. A. F. Philips of Eindhoven, Netherlands, and exhibited at the Oudheid Museum, Amsterdam, in the late 1930s (note) and in Los Angeles from 1992 to 1997.

2. Areas of loss and modern restorations have altered the contours of the lower legs.

3. Bothmer 1960, p. 29, pl. 22, fig. 51.

4. Roeder 1943, p. 274-75, figs. 27-28. Roeder describes the method of attachment and provides a sketch of an attachment mechanism. However, technical examination at the Conservation Center of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, including X-ray radiography, which confirmed the prescience of the tang, did not reveal supporting evidence for the proposed attachment mechanism. In fact, technical evidence suggests that the crown may be a replacement, either an ancient repair or an addition of a modern crown in a modern restoration procedure.

5. Reported by Roeder 1939, p. 275, another bronze image with the same method of attachment as the Shumei bronze is a figure of the crocodile-headed god Sobek, Berlin Museum 2472.

6. Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museum, no. 1943.1121a,b.

7. Roeder 1956, pp. 75-87.

8. Cairo, Egyptian Museum, no. 38598: Daressy 1905, pl. 34; and Roeder 1956, p. 75, 84.

9. Roeder 1939, p. 275