ファラオ頭部(おそらくアメンホテプ3世)

- エジプト

- 紀元前1401-紀元前1363年

- ガラス

- H-16.8

概説

古代では、3次元的なガラス彫刻作品は珍しい。わずかな数しか残っていないのも運命というものだろう。ガラスを専門とするあるエジプト学者が、エジプトから出土したと知られるガラス作品のすべてをその著書で公表してから40年以上が経過したが、いまだに彼の著書が基本的なカタログとして使われている2)。その後、数点のガラス作品が現れたが、出版物で発表されたものはほとんどない3)。

前第2千年紀あるいは前1千年紀、ガラスは貴重で高価な素材であり、その製造は厳しい監視の下で行われていた。時に、出来上がったガラスは硬い石を加工する彫刻家に回され、立体的な作品に仕上げられていった。MIHO MUSEUMが所蔵するガラス製の頭部は、このような珍しい作品の1つである。ガラス彫刻作品は、近東ではさらに珍しい。さまざまな発掘現場からアスタルテ女神の姿を模した古代のペンダントが見つかっているが4)、これらは造りが単純で、オープンモールドで型押ししただけの作品に過ぎない。製作年代は前15世紀半ばから前13世紀である。これらの作品と本作品との関連性はほとんどなく、わずか象嵌と表面に付いている装飾物5)にその片鱗を見つける程度である。このことは、当時、ガラスは主に石や木で作られた彫像を飾るために使われたことを示している。今日まで、近東では、前1千年紀の後半でも全面的にガラスで彫像が作られていたということを示す証拠は発見されていない。

前1千年紀末期、吹きガラス技術が開発され、これをきっかけにガラスは一般的な素材として人気を博するようになるが、この時代でもガラス彫刻作品が作られていたことを示す証拠はほとんどない。黒ガラスで作られた馬の前脚が残っているが、これがローマ彫刻ではガラスを記念碑的レベルで使用していたことを示唆する、唯一の証拠である6)。ギリシアの有名な彫像であるクニドスのアフロディテ像を模した小さな像が2体7)知られている。さらに、興味を掻き立てるようなアウグストゥス皇帝の頭部の小さな彫像や、ガラスでできた豊富な種類の歴代皇帝の頭部が存在している8)。また、数千点の象嵌と数百点の特に贅沢な容器から、ローマのガラス職人の卓越した技を見てとることができる。紀元後のおよそ2000年間を通じても、文献や考古学的研究からガラスを3次元的彫刻作品の材料として確立できる事実は少ない。

このことを念頭に考えると、エジプトで発掘されたほぼ実物大のガラス製の本作品は、ガラス史上極めて重要であると言えよう。エジプトをガラス製造の最先端の地と仮定するならば、ガラス製の頭部は、エジプトのガラス芸術の最高傑作と言えるであろう。この作品は、現在、ニューヨークのメトロポリタン美術館が所蔵している、恐らくネフェルティティもしくはキヤであろうと思われる女王の頭部をかたどったイエロー・ジャスパーの作品9)の驚くほどの美しさを思い出させる。ガラスで作られた他のエジプトの彫刻作品も美しいが、小品である。この作品は、欠損はあるが、質の面で、第18代王朝の時代に作られた王家に関係のある玉石彫刻のうち最高の作品に匹敵する。

記述10)

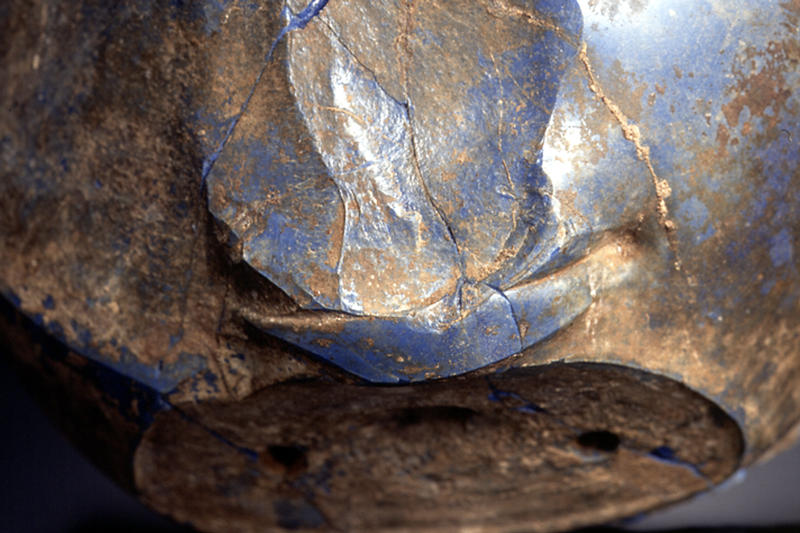

このガラスは、不透明メディウム・ブルーで、気泡がほとんど入っていない。透明なのは縁の部分だけである。このことは、濃く色付けされたことを示している11)。コーニング・ガラス博物館のロバートH.ブリルの化学分析によると、その構成要素はマルカタから発掘された第18王朝のガラスと矛盾しないことが確認された12)。表面には、少し砂が混じったメディウム・ブラウンの石灰質の付着物がまだらに見られる。この層に似ているが実は異なるのが、顔の元々作られた表面に見られるライト・ブラウンからメディウム・ブラウンの薄いガラス性の層である。これは、砂糖の粒子のような失透層のようで、ニスや透明のシェラックなど、表面についた汚れのように見える。この層の下には、薄い外皮の下で不規則に走る直線状の裂け目または縞文様と、本体に入ったひびがある。このような裂け目は、大きな塊の部分と目をその大きな部分に固定したものの接続面で、大きな部分にだけ発生している。縞文様は塊全体に不規則に走っているが、特に中央部に集中しているように見える13)。

失透現象が起きたことを示す他の証拠は、ガラス内部に存在する。頬から剥がれ落ちている楕円形の部分14)は、白い結晶構造をもった光沢のある厚い斑点でおおわれている。これらの斑点が、表面の薄い乳白色の層に広がっている。私が知る限り、これに匹敵する表面をもつ作品もやはりエジプト製である。ツタンカーメンの黄金のマスクに付いていた偽の顎鬚15)は、灰色がかった青ガラスの象嵌であった。表面はやはり変成しており、多分、鬚を顎に固定するためだったのだろうろう、熱を加えられた形跡がある。色を失っているのは、結晶化が原因の失透現象と思われる。

一番大きい部分16)の大きさは、先端を切り取ったフットボールよりも若干小さい程度である。頭の部分は平らになっているが、ここには、かつて額と王冠があり、頭骨の下の部分までつながっていたのだろう。そこに首が付いていたと考えられる。この部分には、さらに、端整な頬の右下部分と下唇のほんの一部が残っている。後側は平らで、その中央には、王冠または鬘から伸びたほぞを固定するための大きな穴があいている17)。メトロポリタン美術館に収められたジャスパー製の彫像片の裏側にも、胴部に固定するための同様のほぞ穴が見られる。彫像の頭部を溝で胴部に固定した可能性は低い。二番目に大きい部分18)は、端整な顔の左側で、額の一部、眉毛用の溝、象嵌の目、頬、さらに上下唇の一部も残っている。頬下部の表面には剥がれ落ちた個所があるが、この部分は、後で接続している。

三番目に大きい部分、すなわち一番小さい部分19)は、小さな楔形をしており、下唇の3分の2を残している。これらの3部分を集めると、唇から下の部分が完成する。これは、大体三角形をした平らな面で、楔形の部分から顎の裏の塊に抜ける3つの穴がある。平らな面は、下唇の真下から始まり、鋭い対角線を描いて、首へと降りてゆく。まるで意図的に顎を削り取ったように見える。

独立している2つの部分の大きい方は、直線の短い2辺と著しくカーブした長い1辺を有する三角形をしている20)。研磨した表面には、平行に走る19本の溝と、長い辺を明確に定めるカーブした線がある。カーブした辺と1本の平行線には、研磨による仕上げを施している。下部の端は直線状であるが、これに関しては、仕上げを施した表面なのか、平らになった割れ目なのか定かではない。もう1つの大きな独立した部分21)は、カーブした細片であるが、比較的直線に近い端は、仕上げを施した表面を示しているようである。表側はきれいに研磨しているが、裏側の表面は粗く、仕上げを施していないのは明らかである。

技法

さまざまな証拠から、エジプトの職人は、固い石や黒曜石を簡単に加工する技術を有していたことが想像される22)。ロスト・ワックス法も関連する華やかな分野の職人は心得ていた23)。このような技術が存在する中で、ガラス工芸職人が、膨大な労力と材料費を費やして頭部をガラスの塊から彫り出したのは驚きである24)。顎の上にある三角形の部分に沿って存在するはっきりした線または隆起部、さらに、頭骨の下と首のラインに沿って存在する類似の隆起部は、鋳造の段階で作られたもので、その後、手を加えていない。この頭像は、ロスト・ワックス法を使って、複数の部分に分けて成形したのであろう。

偽鬚を付けていたと見られる顎のところに存在する平らな面の表面は、その中央部分は比較的粗くでこぼこしている。逆に、外側の端は注意深く磨かれ、なめらかになっている25)。これは、ガラスとガラスを接続したことを示している。額の最上部にはこのような隆起部は見られない。この部分は完全な形で保存されなかったのか、もしくは、より加工しやすい素材で王冠か鬘を作り、それを取り付けていたのではないかと思われる。この像は、複雑であり、大きいので、職人が1つの鋳型を使って製造を試みるよりも、始めから複数の小さな部分に分けて成形したと考える方が妥当であろう。

顎の部分を頭部に固定するための中央の穴は、まだガラスが熱い時にあけられた。端が変形しているからである。両側にある小さめの穴も丸みをおびた端を有している。これは、ガラスが軟らかいうちに作られたことを示すものである。しかしながら、各部を細かく調べてゆくと、研磨剤を入れたある種の穴あけドリル(直径0.5センチ)を使って穴を大きくしたことが確認できる26)。穴の中から透明の赤茶色をした樹脂素材と繊維性の黒い小さな棒が発見された。分析をすれば樹脂素材は多分ピンを所定の場所に固定するために使われたものであることがわかるであろう。そして、繊維性の棒は、ピンの1つであると想像できる27)。上記のドリルは、一番大きい部分の裏側のほぞ穴を作り、大きくする目的にも使われた。

目の穴と眉毛用の溝は、蝋の原形に彫られ、まだ素材が軟らかいうちに形を整えた。象嵌のように嵌め込んだ目は、黒ガラスとアラバスターでできており、灰色がかった緑色をした素材で留めている。この素材は、ガラス製の素材でも樹脂製の接着剤でもない。また、顎の穴に見られた赤茶色の樹脂素材とも異なっている。目を目の穴に固定するには、黒い瀝青質の素材が使われた。角膜と網膜は、磨き上げたのではなく、製造過程で引っ掻いて作られたようである。青いガラスの表面には研磨した跡が見られないが、それでも、この彫像が、鋳型で成形した後に火を使って磨いたとは考えにくい。

調査により、この頭部は、ロスト・ワックス法で複数の部分に分けて製造されたことがわかった。成形した後は、焼きなまし、または冷却を長い時間かけて行ったに違いない。このような大型のガラス彫刻作品を作る際は、納得のいく方法である。それでもなおかつ、かなり時間が経過してから、結晶化現象が現れ、これが原因で、作品が壊れ、時間が経つうちにいくつかの部分に分解したのである。成形と焼きなましが完了した後、各部は木製のだぼと樹脂製の接着剤で機械的に結合された。ガラス製の眉と目は、瀝青で固定した。表面は、回転する道具を使ってきれいに磨き上げた。像の他の部分はガラスで作られていたであろうが、この作業は、多分、鍍金した木製の部品を像に接合するために行われた。

様式と年代

作品が各部に分割されていると、様式と年代の認定が難しくなる。しかしながら、この作品は、その質から考えて、新王国、それも第18王朝の時代の極めて重要な人物のものであると想像できる。彫像の大きさや頬の部分の質量などを考慮に入れると、その人物はハトシェプスト時代以降の人ではないだろうかという説に行き着く。この頭部に匹敵する作品は、コーニング・ガラス博物館が所蔵しているアメンホテプII世の小さな頭部のみである28)。 大きい頭部の唇は、その目と同様、アメンホテプII世の唇や目と異なる。コーニング・ガラス博物館にある頭部は、もっと若く、形式ばっていない印象を受ける。

鼻と頬の接続個所と目の構造の部分にある平らな面は、アメンホテプIII世の典型的な特徴と一致する29)。アメンホテプIII世の唇は、3次元的な彫刻作品でさまざまな形に作られている。1本の細い線で上下唇の輪郭を表す場合もある。いずれにしても、全体的な顔の特徴は、本作品のそれに一致する。また、カルナクのアムン神の顔30)にツタンカーメンの顔との類似性が見られることも述べておかなければならない。このツタンカーメンをより様式化した頭部の作りは、欠損があるために本作品の頭部に近いと映るだろう。しかし、この彫像の重要性とその用途に目を向けた時、モデルはツタンカーメンよりも影響力がある支配者だったと考える方が自然であり、ゆえに、その人物はファラオであったアメンホテプIII世ではないかという説が出てくるのである。実物大の彫像に付けられたガラスの頭部、この唯一で類いまれなる作品は、更なる様式的、科学的研究を必要としている。そのエジプトのガラス史、第18王朝の彫像の研究における重要性は強調してもしすぎることはない。この解説は古代ガラス史の新しい一章のための導入部にすぎないのである。

シドニー・M・ゴールドスタイン

参考文献:

・American Research Center in Egypt, Catalogue of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities at Luxor, Cairo, 1979

・Dan P. Barag, Catalogue of Western Asiatic Glass in The British Museum, vol. 1, London, 1985,

・Robert H. Brill, Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses, 2vols.,Corning, 1999.

・John D. Cooney, "Glass Sculpture in Ancient Egypt," JGS 2, 1960, pp. 10-43.

・Sidney M. Goldstein, "A Unique Royal Head," JGS 21, 1979, pp. 8-16.

・Sidney M. Goldstein, Pre-Roman and Early Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, 1979

・Donald B. Harden et al, Glass of the Caesars, Olivetti, Milan, 1987

・William C. Hayes, The Scepter of Egypt, Part II, Cambridge, Mass., 1959

・Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Winter 1983-1984, Egyptian Art, New York 1984

・Axel von Saldern, Ancient Glass in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1968

註:

01. 表面を様々に仕上げた3つの欠片があるが、その1つは2つの大きな断片が鼻の付け根あたりで合わさる部分に開いた三角形の孔に嵌められ、もう1つは下唇の1cm四方の正方形部分に嵌められ、3つ目は首筋の下の三角形部分に嵌められている。

02. Cooney 1960, pp.10-43.

03. Goldstein JGS 1979, pp.8-16.

04. Barag 1985, pp.45046, nos.15-16, pl.2; 大英博物館の近東のガラスについての論文に最も最近出版された遺跡を掲載; Goldstein, 1979, p.47, no.1.

05. Barag, op. cit. pp.75-77, nos.62-71, pls.8-9.

06. Harden 1987, p.28, no.6.

07. Harden 1987, p.29, no.7, 前記の参考文献参照; Saldern 1968, no.28.

08. Ibid. pp.21-24, nos.1-4 及び前記の参考文献参照。

09. Hayes 1959, p.260, fig.156; Metropolitan Museum of Art 1983, p.33.

10. 著者はこの断片を1989年に調査する機会を得た。その時、双眼顕微鏡で注意深く調査が行われたが、ここに述べる記述と結論はその時の調査記録をもとにしている。最近MIHO MUSEUMを訪れた時は、この品物と短時間再会しただけであった。この重要な彫刻についての考察は、メトロポリタン美術館のDorothea Arnold 博士とChristine Lilyquist博士に負っている。Lilyquist博士はこの彫刻を前に見ている。彼女はこの少数ではあるが極めて重要な石とガラスの彫刻の一群を論文として出版する目的で、大変注意深くそれを研究した。

11. 作品本体には明らかな不純物は見られないが、多くの「栓球」と粗雑な球形の不透明白色の形成物がある。これらは石や融解していないガラス原料ではなく、ガラス本体自体の結晶化による不透化の跡である。この過程は異なる欠片によって様々な段階が観察されるが、この場合は幾分典型的ではないものの、この色のガラスでは知られた現象である。

12. Brill 1999, vol.1, p.36 sample 3389; vol.2 p.39,(for tables). このガラス資料の分析についてBrill博士に謝意を表したい。これはアマルナの第18王朝のガラス工房址から発掘されたガラスよりも、マルカタのものに一番近いと彼は考えている(11/26/1990 の個人的通信による)。

13. この中央の部分の裂溝構造から無水珪酸(?)の結晶が成長しているように見える。実際に、仕上げられた表面と裂溝の表面とは対照的な違いがある。結晶の成長したものは無色あるいは不透明のものから白い半透明のものまである。仕上げられた表面には樹脂のように見える褐色の素材で染まっている物質がある。それは表面全体に特有の色彩を与えているものと同じ物質である。この成長した結晶性の斑文が亀裂を生じさせたのであって、発掘者の道具によって砕かれたためではないと考えたくなる。例え亀裂の原因にはならなかったとしても、これら内部の一番抵抗の少ない「断層線」となったであろう。

14. 長5.8 cm; 高 3.3 cm; 厚 約0.5 cm.

15. 著者はこの作品を実際には調査していないが、1976年にBrill博士とその状態について話し合っている。彼はニューヨーク・メトロポリタン美術館で開催された「ツタンカーメンの宝物」展に出品された多くのガラスの作品を検査した。

16.この頭部は現在の無修復の状態では測定が困難である。現存の高さ16.8cm、後部平面部分の幅16.2cm、奥行10.5cm。

17.後部の溝の側面に沿った欠けあとがこの部分の測定を困難にしている。現存の長さは14cmで、この溝の中間の部分から下に向けて独特の線を描いて明確に細くなっている。溝の中間では幅2.7cmで、下の方は2.4cmである。深さは約1.5cmで「ほぞ」を受けるために鳩尾羽状に切り込まれている。ほぞから強い圧力がかかったかのように、長い三角形のガラス片が溝の上の方から剥がれている。この溝の下にある平らな背面上の矩形の表面とこの断片の底には平行な溝が5本数えられる。このような明確な溝が何のために切られたのか不明である。

18. 現存高17 cm; 現存幅13.8 cm; 厚約4.5 cm。楕円形の欠片が頬から剥がれている。高5.8cm; 幅3.3cm; 厚5cm。

19. 唇の下から上端までの高さ4.8cm; 正面の表面に沿った幅4.6cm; 前部から後部までの厚さ約11cm。

20. 現存高7.4cm; 幅7cm; 厚4cm。この断片に関してのみ概略の寸法をドローイングから取った。

21. 最大高4cm; 幅1.6cm; 厚0.85cm.

22. Goldstein JGS 1979 p.11。特に脚注参照。

23.Goldstein 1979, p.33.

24. Goldstein JGS 1979, p.11.

25. この技法は、ギリシアの石工が建築のために大きな石のブロックを用意したことを思わせる。隣接するブロックと合わせるため、外側の縁のみ注意深く削って磨くのである。中央の部分は低く切って粗いままにし、表面全体を仕上げることを省略するのである。

26. この孔は大きくも深くもなく表面より1.7cm彫り込んだ2つの小さな溝があるかのようである。これらの小さな孔の底は大変違っている。1つは粗く平らではないが、もう1つはほとんどなめらかである。どちらも輪郭を示す溝が底についており丸鑿を使ったように見える。斜めから光で照らすと集中した溝が壁面に見え、このことを確信させる。

27. この棒が孔の中に侵入した樹木の根の部分であるとは思われない。

28. 註2参照

29. American Research Center in Egypt 1979, no.104, p.80, fig.60-61,この拳を握りしめた座像はすぼめた唇が、そのまわりに浅く彫られた溝で強調されている。

30. Ibid, p.127, no.183, figs.

Catalogue Entry

Egyptian, 18th Dynasty, 1400-1350 B.C.

Opaque medium blue glass, inlaid with black glass and alabaster (?).

Lost wax cast, cut and polished.

Three major joining fragments, several smaller joining wedges and chips1); two nonjoining fragments; patches of limely accretion and some evidence of devitirification.

Largest fragment Height 16.8cm, Width (across the back) 16.2cm,

Thickness 10.5cm

An Overview

Three dimensional glass sculpture is rare in antiquity, it may be just chance that so little survives. So, even though it has been more than forty years since an Egyptologist, specializing in glass, published all of the sculpture in glass known from Egypt, his work still remains the basic catalogue2). A few additional works have come to light but not much more has been published3).

In the second and first millennium B.C. glass was a rare and costly material which was highly prized and its production jealously guarded. On occasion, objects seem to have been turned over to hard stone carvers in order to produce a work of three dimensions. The Miho glass head would appear to be one of these exceptions. Glass sculpture is even more rare in the Near East. Early pendants representing the goddess Astarte exist from various excavations4) but they are simple and pressed into an open mold. They date from the mid-15th to the 13th century B.C. The only materials remotely comparable to the Egyptian head are the fragments of inlays and appliques5) which suggest that glass was used primarily to embellish stone and wooden statues. To date, no evidence exists confirming that such statues in the Near East were made entirely of glass even later in the 1st millennium.

With the invention of glassblowing at the end of the first millennium and the subsequent popularity of glass as a common material, little evidence of glass sculpture exists. The foreleg of a horse in black glass provides a single clue that glass was used on a monumental scale for Roman sculpture6). Two small scale copies of the famous Greek sculpture of the Cnidian Aphrodite7) are known. A tantalizing diminutive head of the Emperor Augustus and a somewhat increasing assortment of imperial glass heads are preserved8). Thousands of inlays exist and hundreds of extraordinary luxury vessels attest to the virtuosity of the Roman glassmaker. Yet over this period of nearly two millennia, little evidence either in the literature or from archaeological study exists to establish glass as a medium of three dimensional sculpture.

With this in mind, the existence of a roughly life-size head of solid glass from Egypt is of incredible importance for the history of glass. For Egypt, it must assume a place at the forefront of glassmaking, perhaps as the most significant accomplishment of the Egyptian glassmaker's art. It is reminiscent of the astounding beauty seen in the fragmentary Head of a Queen possibly Nefertiti or Kiya carved in yellow jasper, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York9). Other Egyptian sculptures in glass are beautiful but diminutive masterpieces. This object, though fragmentary, compares in quality with the finest royal stone sculptures fabricated in the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Description10)

The glass is an opaque medium blue containing very few bubbles and is translucent only at the very edge, suggesting intense coloration11). A chemical analysis done by Dr. Robert H. Brill at the Corning Museum of Glass confirmed the glass composition was consistent with 18th Dynasty material excavated at Malkata12). The surface is unevenly covered with a medium brown limely accretion which retains some sandy inclusions. Similar to this layer but distinct from it is a thin light to medium brown glassy layer notably on the original worked surfaces of the face. This seems to be a layer of sugary devitrification and appears as a surface stain like a varnish or transparent shellac. Beneath this layer is a series of straight but random fissures or veins which run under the thin crust and are cracks in the matrix. These fissures occur on the interface between the massive fragment and the piece preserving the eye only on the massive side. Although the veins run randomly through the mass there appears to be a concentration at the center13).

Additional evidence of devitrification exists within the glass. The oval segment14) spalled from the cheek is covered with glossy thick patches of white crystalline structures. These bloom over a thin milky layer on the surface. The only related surface known to me is also Egyptian. The false beard on the gold mask of Tutankhamun15) has greyish blue glass inlays. The surface is also disturbed and may have been heated, perhaps to join the beard to the chin. The discoloration appears to be a result of devitrification.

The largest fragment16) preserves the flat top of the head probably where the forehead and crown joined and ran down to the base of the skull. Here the neck would have been added. It also preserves the proper lower right cheek and a sliver of the lower lip. The back is flat and has a large central mortise into which the tenon extending from the crown or wig was secured17). A similar mortise exists for attachment to the body on the back of the jasper fragment in the Metropolitan Museum. It is less likely that the channel secured the head to the body of the sculpture. The second largest fragment18) preserves the proper left side of the head including a portion of the forehead, eyebrow channel, inlaid eye, cheek and part of the upper and lower lip. A portion of the lower cheek spalled from the surface and was reattached.

The third and smallest fragment19) is a small wedged-shaped element which retains two thirds of the lower lip. Joining the three elements reconstitutes the entire area below the lip. It forms a roughly triangular flat surface with three holes worked through the wedge-shaped fragment and into the mass behind the chin. The flat surface begins immediately below the lower lip and runs back at a sharp diagonal down toward the neck, appearing as if the chin was purposely cut away.

The larger of the two nonjoining fragments is triangular with two short straight sides and a longer markedly curved side20). The polished surface has 19 cut parallel grooves with a cut curved line defining the long edge. The curved side and the one parallel to the lines are finished by polishing. Although the bottom edge is straight, it is unclear if this too is a finished surface or a smooth break. The other large nonjoining fragment21) is a short curved strip with relatively straight edges which may represent finished surfaces. The face is well-polished while the back is left rough and unfinished.

Technique

Evidence suggests that Egyptian craftsmen worked hard stones and obsidian with ease22). The technique of lost wax casting was also known to craftsmen working in related pyrotechnical areas23). It seems incredible that given this technology, glass craftsman would expend the considerable additional labor and material expense to carve the head from a solid glass block24). The distinct line or ridge along the triangular area above the chin and a similar ridge along the base of the skull at the neckline were created during casting and not reworked. The head was cast in several pieces most likely by a lost wax process.

The flat surface at the chin where the false beard might have been attached is relatively rough and uneven at its center while the outer edge has been carefully smoothed25). This suggests a glass to glass join. No such ridge exists at the top of the forehead. Either this area is not completely preserved or the crown or wig was of a material more easily fashioned and affixed. The figure was complex and large enough that craftsmen cast several smaller pieces of glass rather than casting in a single mold.

The central hole used to secure the chin element to the head was enlarged while the glass was hot, the edge is deformed. The smaller holes on either side also have rounded lips, appearing to have been formed while the glass was soft. However, a section examination confirms that some type of hollow core drill (0.5 cm. In diameter) fed with abrasive was used to enlarge the hole26). A translucent reddish brown resinous material and a small fibrous black rod were found floating within the hole. An analysis might confirm that the resinous material was a binder which held the pin in place. The fibrous rod may be one of these pins27). The same drill mentioned above, was used to create or enlarge the mortise in the back of the largest fragment.

The eye socket and the eyebrow channel were modeled in the wax original and were worked when the material was soft. The elements of the inlaid eye, composed of black glass and alabaster, are secured with a grayish green material. It is neither a glassy material or a resinous binder and differs from the reddish brown resin noted in the holes on the chin. A black bituminous material was used to affix the eye unit into its socket. The cornea and retina seem to be scratched during fabrication rather than polishing. There appear to be no polishing marks on the surface of the blue glass and yet it is highly unlikely that the sculpture could have been fire polished after casting.

The examination suggests that the head was lost wax cast in several pieces. Following the casting, the annealing process or slow cooling must have been quite lengthy and well-understood to produce such a large object. Nevertheless, some devitrification occurred and caused the object to fracture and separate over time. After casting and annealing, the pieces were mechanically joined with wooden dowels and resinous binders. The glass eyebrows and eyes were secured with bitumen. The surfaces were finished with rotary and fine polishing.

Style and Date

The fragmentary nature of the object makes a positive identification very difficult. Nevertheless, the quality of the object suggests an extraordinary and important individual of the New Kingdom, probably 18th Dynasty. The mass of the figure and the substantial weight in the cheek would suggest an individual after the time of Hatshepsut. The only parallel which can be cited in glass is the diminutive head of Amenhotep II in the Corning Museum of Glass28). The lips of the large head are different than those of Amenhotep II as is the shape of the eye. The Corning head seems more youthful and less formal.

The flatness at the juncture of nose and cheek as well as the formation of the eye is consistent with the representations of Amenhotep III). His lips are variously treated in 3 dimensional sculpture. A thin line often highlights the outer edge of both lips. Nevertheless, the overall facial features are consistent with the Miho glass head. Finally, The likeness of Tutankhamen seen in the face of Amun at Karnak30) should also be mentioned. This more stylized treatment of Tutankhamen may appear closer to the Miho head because of the head's fragmentary nature. However, the importance of the sculpture and its purpose might suggest a ruler more influential than Tutankhamen and thus the suggestion of Amenhotep III as the pharaoh represented. The existence of a glass face from a life-size composite statue, a unique and extraordinary object will require much additional stylistic and scientific study. Its importance to the history of glassmaking in Egypt and to the understanding of 18th Dynasty sculpture cannot be overstated. This entry is only an introduction to a new chapter in the history of ancient glass.

Dr. Sidney Merrill Goldstein

Bibliography:

・American Research Center in Egypt, Catalogue of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities at Luxor, Cairo, 1979

・Dan P. Barag, Catalogue of Western Asiatic Glass in The British Museum, vol. 1, London, 1985

・Robert H. Brill, Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses, 2vols.,Corning, 1999.

・John D. Cooney, "Glass Sculpture in Ancient Egypt," JGS 2, 1960, pp. 10-43.

・Sidney M. Goldstein, "A Unique Royal Head," JGS 21, 1979, pp. 8-16.

・Sidney M. Goldstein, Pre-Roman and Early Roman Glass in The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, 1979

・Donald B. Harden et al, Glass of the Caesars, Olivetti, Milan, 1987

・William C. Hayes, The Scepter of Egypt, Part II, Cambridge, Mass., 1959

・Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Winter 1983-1984, Egyptian Art, New York 1984

・Axel von Saldern, Ancient Glass in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1968

Notes:

1. There are three chips which fill various finished surfaces. One fits into a triangular loss where the two large fragments meet near the base of the nose. A one centimeter square chip fills a place in the lower lip and another triangular fragment fits a loss on the base at the neck line.

2. Cooney 1960, pp. 10-43.

3. Goldstein JGS 1979, pp. 8-16.

4. Barag 1985, pp. 45046, nos. 15-16, pl. 2; most recently published the sites in conjunction with his work on the Near Eastern Glass at the British Museum, see also Goldstein, 1979, p. 47, no. 1.

05. Barag, op. cit. pp. 75-77, nos. 62-71, pls. 8-9.

06. Harden 1987, p. 28, no. 6.

07. Harden 1987, p. 29, no. 7, see earlier bibliography; for the second example in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Saldern 1968, no. 28.

08. Ibid. pp. 21-24, nos. 1-4 and bibliography.

09. Hayes 1959, p. 260, fig. 156; Metropolitan Museum of Art 1983, p. 33.

10. This author had the opportunity to examine the fragments in early 1989. At that time a careful examination of the fragments was done with the aid of a binocular microscope. The descriptions and conclusions presented here were based on notes from that exercise. My recent visit to the Miho Museum allowed only a brief re-acquaintance with the object. I am indebted to Dr. Dorothea Arnold and Dr. Christine Lilyquist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York for their thoughts on this important sculpture. Dr. Lilyquist saw the piece sometime ago. She has studied it quite carefully with the intention of publishing an article on this small but extraordinarily important group of composite statues in stone and glass.

11. There is no apparent impurity within the body of the object but there are numerous "platelettes" and roughly spherical opaque white formations. These do not appear to be stone or unmelted batch material but rather traces of devitrification within the body of the glass itself. This process is seen in varying stages by examination of different fragments, again rather atypical but not unknown for this particular color.

12. Brill 1999, vol.1, p. 36 sample 3389; vol. 2 p. 39, (for tables). I am grateful to Dr. Brill for his analysis of the glass sample. He felt that it most closely resembles Malkata material rather than glass excavated from the other 18th Dynasty glass factory site at Amarna; per correspondence 11/26/1990.

13. Crystals of silica (?) appear to be growing out the fissure structure in this central location. In fact, there is a marked contrast in the fissures on this surface with those on the finished surfaces. Here the crystalline growth is colorless or opaque to translucent white. On the finished surfaces the material is stained with a brown resinous-looking matter. It is the same material which gives the characteristic color to the overall surface. It is tempting to suggest that the growth of this crystalline pattern may have caused the piece to fracture rather than a blow from the excavator's tool. If not the cause for the fracture, perhaps these internal "fault lines" determined the paths of least resistance.

14. Length, 5.8cm; height, 3.3cm; thickness, ca. 0.5cm

15. The author has not examined this object in person but had discussed its condition with Dr. Brill in 1976. He had examined many glass objects exhibited in the "Treasures of Tutankhamun" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

16. The head is difficult to measure in its present unrestored state. The preserved height is 16.8cm.; the width across the flat back is 16.2cm; the depth is 10.5 cm

17. The chips along the sides of the back channel make the measurements of this element difficult. The preserved length is 14cm with a distinct taper apparent from the middle to the base of the element. At midpoint, the channel is 2.7cm wide tapering at the base to 2.4cm. The channel is about 1.5cm deep and is cut as a dovetail to receive a tenon. Long triangular strips of glass have snapped away from the upper sections of the groove as if extreme pressure on the tenon sheared these elements. The rectangular surface below the channel on the flat back and at the base of the fragment is scored with five parallel grooves. Why these purposeful grooves are cut here in unclear.

18. Preserved height 17cm; preserved width 13.8cm; roughly 4.5cm thick. An oval shaped fragment has spalled from the cheek; height, 5.8cm; width 3.3cm; thickness 5cm

19. Height from bottom of lip to top edge, 4.8cm; width along front surface, 4.6cm; depth from front to back, ca. 11cm

20. Preserved height, 7.4cm; width, 7cm; thickness 4cm: approximate measurements taken from drawings for this fragment only.

21. Greatest dimension, 4cm; width, 1.6 cm; thickness, 0.85cm

22. Goldstein JGS 1979 p. 11 especially footnotes.

23. Goldstein 1979, p. 33.

24. Goldstein JGS 1979, p. 11.

25. This technique reminds the author of the way in which Greek stone craftsmen prepared large blocks for architecture. Only the outer edge was carefully ground and polished to receive the adjoining block. The central area was cut lower and remained rough in order to eliminate the extensive final finishing of the entire surface.

26. The hole was not large or deep enough as there were two smaller channels drilled into the surface 1.7cm. Deeper than the original floor. The floors of these smaller holes are quite different. One is rough and uneven while the other is almost smooth at the base. Both have a circumscribed groove at the base suggesting that a hollow core drill was used. In raking light concentric grooves can be seen on the walls reinforcing this suggestion.

27. Less likely, the rod may represent a segment of tree root that grew into the hole.

28. See above, footnote 2.

29. American Research Center in Egypt 1979, no. 104, p.80, fig. 60-61, this seated figure with clenched fist has characteristic pursed lips with a light groove carved around the outside to form a highlight.

30. Ibid, p. 127, no. 183, figs. 99-100.