金帯

- メソポタミア/イラン西部

- 紀元前8-紀元前6世紀

- 金

- H-51.5 W-5.8

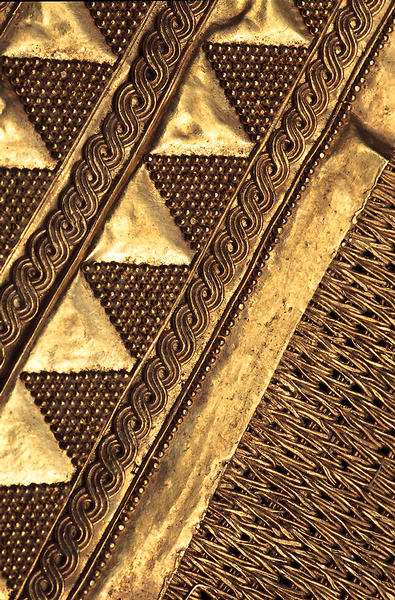

これらの三本の金帯は、金の薄帯をねじり、紐状になったものを加熱して接点を融合させ、多数の小環に作り緯を芯に編み上げたものです。

両端をおさえる幅の広い金板はグラニュレーションで構成した三角形と菱形、及びギルロッシュ形に貼り付けられた金糸で装飾されています。

特にこの両端の意匠は紀元前二千年紀のエジプトに由来し、当時エジプトと盛んな交易のあったカッシートの装身具に秀明帯に極めて近い意匠が見られます。

・Christiane Desroches Noblecourt/ Tutankhamen/ 1963 New York Pl. XXIa;

・ William Culican / The Medes and Persians / 1965 New York; ・K.R.Maxwell-Hyslop/ Western Asiatic Jewellery c.3000 -612B.C./ London 1971;

・7000 Jahrre Kunst in Iran / 1962 Essen ;

・Carol Andrews / Ancient Egyptian Jewelry / 1990 London

グラニュレーション

粒金と金線の細工は古くは紀元前三千年紀メソポタミア・ウルの王墓にみられますが、とりわけエジプト第18王朝トゥトアンクアメン、第19王朝ラムセス二世の王墓からは類似の金線と粒金細工を組み合わせた宝飾品がみつかっています。

またこの帯と同時代のメディアのものとされる金のメダイオン及び犠首にも同様の技法が見られます。

この粒金法(グラニュレーションgranulation)と呼ばれる古代技法は

1.あらかじめ等しい大きさに刻んだ金板の小片を融解点まで熱し、金の小粒を作る。

2.水酸化銅と有機物の混合した糊を使い、1.の小粒を装飾すべき金の表面に接着し、文様を作る。

3.これを金の融解点以下に熱すると有機物は酸化し炭化され、水酸化銅を還元して金板の表面と粒金の表面を銅の点状のはんだで接合することとなる。

この技法は紀元数世紀のうちに消滅し、今世紀後半になって「発見」され復元されました。

・Christiane Desroches Noblecourt/ Tutankhamen/ 1963 New York Pl. XXIa;

・ William Culican / The Medes and Persians / 1965 New York; ・K.R.Maxwell-Hyslop/ Western Asiatic Jewellery c.3000 -612B.C./ London 1971;

・7000 Jahrre Kunst in Iran / 1962 Essen ;

・Carol Andrews / Ancient Egyptian Jewelry / 1990 London

人物文様杯

猛禽文様杯

牡牛装飾脚杯

Catalogue Entry

The first fine-mesh strap, A, has wide flat terminals decorated with a fine network formed by a row of diamond-shaped patches of granulation framed by inward-pointing triangular patches of granulation. The edges of this arrangement are bordered by two guilloches of gold wire with an additional row of granulation along each outside edge. Four nearly circular attachment rings with somewhat flattened bases are fused to the edge of each terminal. The gold strap is made of interlocking loops of hand-made, twisted and heated wire woven in a double loop-in-loop chain on a "weft" of long narrow gold loops. Damage to the strap visible in lines of bent and compressed links show that the strap was folded into a small packet and apparently was under pressure for some time. The lines suggest that the band was folded back and forth in a roughly accordion-like manner. It was not folded in half symmetrically and then in quarters.

The second example, B, the widest of the straps, has terminal plates with two rows of outward-pointing triangular patches of granulation. These triangles are framed by three guilloches of three wires each bordered by straight lines formed by a single thin gold wire. The outermost edge of the plate where the fastening rings are attached has a now-fragmentary line of fine granulation. A similar, better preserved line of granulations also marks the edge of the decoration on the strap side. The effect of the arrangement is visually bolder and stronger than the interlocking pattern of the first belt. Compression patterns suggest that this band was folded in thirds for a prolonged period. This very wide band is further damaged with noticeable longitudinal tears along the upper and lower edges of the strap.

The third strap, C, narrow and slightly longer than the other two, is the least damaged of the three. The metal of the terminal plates is thick and has a single row of triangular patches of granulation on the edge adjacent to the strap. The granulation was irregularly set; the loss of some granules erodes the precision of the ornament. The triangles point toward the outer edge of each plate from a baseline defined by two rows of strip-twisted wire between smooth wire borders. Three loops (one of which is now missing) secured each end of the band to its backing. These loops, thicker than the loops on the other two bands, have an almost semicircular shape which further distinguishes this piece.

The production of gold straps, that is, parallel chains that are also linked to each other in a variety of ways to form a broad and flexible textile-like material, is best known in the Aegean where from the fourth century B.C. onwards gold strap necklaces were produced. Recent discoveries in northern Mesopotamia, however, show that gold straps were produced there as early as the eighth century B.C.1 While the manner in which the Shumei bands were formed has Aegean parallels, the terminals of the bands, or belts, point to a Near Eastern rather than Aegean origin. Double guilloche borders rendered in applied wire and rows of triangular and diamond-shaped patches of granulation have a long history in West Asian metalwork. They do not appear on classical jewelry, which display curvilinear floral and vegetal forms even when produced for West Asian patrons.2 Geometric decoration based on granulation rather than filigree is a common feature of the ornamental gold caps on some ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals and jewelry as early as the mid-second millennium B.C.3 Likewise, the use of a double guilloche to border the granulated zones also has Mesopotamian parallels of the mid-second millennium B.C. and Iranian examples of the twelfth century B.C.4 Excavated jewelry from the Neo-Assyrian period (ninth-seventh centuries B.C.) in Mesopotamia features both diamond-shaped patches of granulation and borders of smooth and strip-twisted wire.5 Thus both the double loop-in-loop technique itself and the decorative patterns of the terminals are not dependent on the Aegean goldsmithing tradition. The simple fusing of the strap to the terminal plates also shows no influence from the Greek tradition, which features mechanical joining by means of pins and/or hinges often protectively covered by a box-like enclosure usually with a tapered profile.6 Similarly, the circular and nearly circular loops fused to the terminal plates do not have Greek parallels.

The treatment of gold wire as if it were thread occurs in Anatolia as early as 1800 B.C.,7 and examples of fiber thread wrapped with precious metal and then woven to form a golden cloth are known from later periods in the Near East.8 Nonetheless, no close excavated parallels to the Shumei bands are known. Two smaller and more damaged straps are without archaeological context.9

Likewise the manner in which these bands were used is uncertain. Clearly they were too fragile to be worn by themselves, secured only by laces through the loops, but needed the support of a stronger backing like textile or leather. Since there is no archaeological context for these works, we cannot be sure that they were worn as belts, that is at or around the waist. Indeed it is possible that they were not meant to be worn by humans at all, but were part of some divine regalia. Golden ornaments and clothing for divine images are well-documented in Mesopotamia in the first millennium B.C.10 No comparable written evidence exists for western Iran, but one may assume a general parallelism.

TSK

1. Williams and Ogden 1994, p. 26. See also Harrington and Lyons 1990, pp. 48-53.

2. Williams and Ogden 1994, nos. 53, 64, 84, 121, pp. 99, 112-13, 142, 188-89.

3. Lilyquist 1994, p. 15, fig. 21j-l, p. 16, fig. 22, pp. 19, 25-27. See Collon 1987, pp. 50-51, nos. 198-99; and Lilyquist 1993, p. 77, fig. 6c, for impressions of cylinder seals having caps decorated with granulated triangles.

4. Maxwell-Hyslop 1971, pp. 164, 187, pls. 127, 134.

5. Ibid., pp. 233-35, pls. 216, 218.

6. Williams and Og